The fifteen crisp and sophisticated color images of Paris and Rome included in the exhibit become the setting for Bossaglia’s renewed quest to explore urban landscapes and investigate the fabric of metropolitan life. The shots extend his previous work and are, once again, visually impeccable.

In his critical essay Francesco Faeta observes:

“Although Bossaglia’s images appear sharp and conceptually strict, his methodology in achieving them is built on a wandering apprehension of the cityscapes, one that draws on Baudelaire or Benjamin’s flâneur. His meandering brings him to indulge in accidental encounters and adopt a vagrant’s openness; nonetheless, he also consistently retains a contemplative distance from the subject he observes (and what is most striking, one might add, is his ability to juggle these viewpoints thus generating images that are thought-provoking and original).

Rome and Paris (as all other western cities) are colored with the work of ‘writers’ or graffiti artists. Although the phenomenon is widely documented and studied, Bossaglia’s approach is markedly new. He is not interested in graffiti as a reflection of urban anthropology or of a broadening of artistic media, but rather he investigates it as a specific and original art-form that can reshape our experience of the network of enlacing streets that constitute cityscapes. The graffiti redefine marginal buildings and rewrite suburbs and slums, changing all those non-spaces (Marc Augé) that weave the fabric of daily city life.

The human beings in this collection are few and far between; they are also, however, essential as they color the background of the thick urban web. In their ephemeral presence, they often define the poetic attention to detail mentioned earlier. The people in the pictures enhance our notion of the expanse of space portrayed while highlighting the solitude it projects on them. Indeed, the people are more likely to interact with the shapes and curvatures of buildings than with other human beings and are thus reminiscent of the solitude of prime numbers, to cite Paolo Giordano. Mathematicians call such numerical entities twin primes (…) couples of prime numbers that are almost in proximity, if there weren’t another number between them forever forbidding them from touching.

Bossaglia does not reveal the secret behind such isolation; he does, however, take our hand and guide us to our own discovery of a new piece of the metropolitan puzzle. He does so with the craftsmanship of a true poet.”

Selected works

Gallery

Critical essay

Encounters

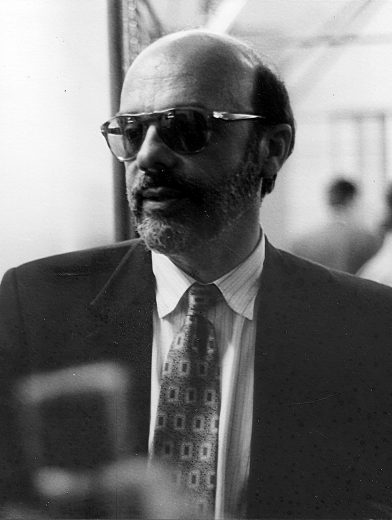

by Francesco Faeta

Roberto Bossaglia’s most recent collection of photographs, exhibited at Maja Arte Contemporanea, stands out for the sharp and refined quality of the images presented. Such quality comes from the artist’s desire to represent metropolitan life and urban landscapes with utmost visual rigor. Bossaglia has pursued this vision for a long time, and this has brought him to photograph many different cityscapes (including: Naples, Rome, Turin, Milan and its surroundings, Paris, Munich). In each of these cases, his glance has been moved by his longing to explore the city’s expanses practically, pausing on its architecture and considering it as a reflection of its inhabitants. The pictures depicting Rome and Paris mark the more urbane pages of this investigation, which both continues the discourse of his previous work and breaks away from it by developing new and innovative techniques. This gives the shots an almost marvelous quality.

I will try to give an overview of the body of Bossaglia’s urban work first, and then highlight its most original and distinguishing features.

In order to appreciate Bossaglia’s vision fully, one must bear in mind the cultural and technical lens through which he broaches cityscapes. Bossaglia has a background in math and science and thus has a structuralist approach towards the world he represents. This enables him to use the camera as both an analytical tool and as a tool to synthesize space. Bossaglia also has extensive and noteworthy experience as an architectural photographer, which trained his eye and taught him to apply his technical skills rigorously. His work can, in fact, be considered twofold. He both works on commission, producing technically sharp shots of architecture aimed at documenting reality, and he works to express his own artistic vision, exploring architectural shapes as a manifestation of dreams and ideals. Even in the latter shots, though, his glance remains essential, grazing technical perfection (he chooses to, for instance, enhance the western light touching Roman walls by using paper he specifically treated to bring out colder hues, golden nuances, or gray tones, or to reproduce the Parisian cityscape by using wide lambda prints, with a en plein air sharply-focused shot). At first glance, this precision can induce viewers to believe they are confronted with a specialized and realistic reproduction or documentation of cityscapes. This conviction, however, is easily overturned when one notices and reflects upon Bossaglia’s use of sophisticated cultural allusions and citations throughout the images. Years ago, Cesare De Seta was – I believe – the first to point out the particularly constructed style of Bossaglia’s images and to isolate their focus on architecture as their defining feature. I find that this is still true of the images presented today. Bossaglia’s interpretation of space defies mere reproduction or documentation and instead ventures to become a conceptual model of reality, one that seems to stem from Wittgenstein’s study of the power of visual images in constructing our imagination. His photographs delve into the notion of space which underlies architectural design and urban planning; for this reason among others, they become an interesting lens through which to explore urban anthropology.

Although Bossaglia’s images appear sharp and conceptually strict, his methodology in achieving them is built on a wandering apprehension of the cityscapes, one that draws on Baudelaire or Benjamin’s flâneur. His meandering brings him to indulge in accidental encounters and adopt a vagrant’s openness; nonetheless, he also consistently retains a contemplative distance from the subject he observes (and what is most striking, one might add, is his ability to juggle these viewpoints thus generating images that are thought-provoking and original).

As is known, Baudelaire is the first to define the nature and role of the flâneur (if implicitly), and to create a correlation between him and the questions raised by our urge to represent reality. He identifies the problems posed by the modern city – in his case Paris – with respect to literature and the arts uncovering the checkmate position urban life places both in. He then postulates the need for a détaché perspective in order to tackle the uncontrollable pace of the metropolis as well as its deluding ability to expose and conceal things from the people populating its streets. The flâneur wanders through the city’s streets allowing them to carry him as would a labyrinth; the city thus acquires a shifting quality, with its focus changing with each step and its shape metamorphosing each time a corner is turned. The flâneur observes all this idly; yet this same idle distance allows him to seize and reflect upon the city’s most secret recesses. Baudelaire sees the flâneur as a key figure which can help renovate the artistic experience: he can navigate cityscapes freely and he is also an improvised ethnographer. Indeed, the beauty of his ethnography is its freedom from schematic needs and thematic constrains.

Benjamin broaches the idea of a flâneur by revisiting Baudelaire’s vision and reinterpreting it. His flâneur is the only possible explorer of the urban cityscape. He envisions him as the person charged with a historical awareness of the places he is observing mixed with the ability to evaluate their shapes and substance by discovering unprecedented connecting points or points of discord. His wandering allows him to experience such connections directly.

In Bossaglia’s work one may find deliberate echoes of Baudelaire’s poetic vision of cityscapes mingled with Benjamin’s (perhaps this is the key to the marvelous elements I mentioned earlier). In these Encounters (the name Bossaglia aptly chose for the collection), I have found all of the elements that I summarized above. However, the images are also charged with the innovative and original quality I mentioned in the opening of this piece.

In this collection, Bossaglia changes the scale of his images; he indulges in details. This is reminiscent of Warburgian ideals (‘God resides in details’) on the one hand, but also produces a distancing effect which is absolutely original in its application to the urban landscape. Rome and Paris (as all other western cities) are colored with the work of ‘writers’ or graffiti artists. Although the phenomenon is widely documented and studied, Bossaglia’s approach is markedly new. He is not interested in graffiti as a reflection of urban anthropology or of a broadening of artistic media, but rather he investigates it as a specific and original art-form that can reshape our experience of the network of enlacing streets that constitute cityscapes. The graffiti redefine marginal buildings and rewrite suburbs and slums, changing all those non-spaces (Marc Angé) that weave the fabric of daily city life.

Commenting on the use of details in discussing long-shot pictures or pictures shot with wide angles might seem paradoxical. It is essential, though, because the details in Bossaglia’s photographs remain remarkably visible with respect to their context; they maintain an independence from the whole and nod to the other details present, which the photographer so deftly arranges.

The human beings in this collection are few and far between; they are also, however, essential as they color the background of the thick urban web. In their ephemeral presence, they often define the poetic attention to detail mentioned earlier. The people in the pictures enhance our notion of the expanse of space portrayed while highlighting the solitude it projects on them. Indeed, the people are more likely to interact with the shapes and curvatures of buildings than with other human beings and are thus reminiscent of the “solitude of prime numbers”, to cite Paolo Giordano. Mathematicians call such numerical entities twin primes (…) “couples of prime numbers that are almost in proximity, if there weren’t another number between them forever forbidding them from touching“.

Bossaglia does not reveal the secret behind such isolation; he does, however, take our hand and guide us to our own discovery of a new piece of the metropolitan puzzle. He does so with the craftsmanship of a true poet.

(Translation by Livia Sacchetti)