Maja Arte Contemporanea is delighted to host the first solo exhibition by sculptor Angela Maria Piga; on this occasion, she offers her audience a selection of sculpted ceramics, created in 2017-2018 and displayed here for the very first time.

Born in Rome in 1968, Angela Maria Piga comes to sculpture after a life dedicated to writing and curating exhibits. She started her career by working in an art gallery, then went on to write about art and architecture. Having spent twenty years observing art created by others, she decided to venture into new territory and – in her own words – move “from observation to action,” beginning her intense work with ceramic in 2017.

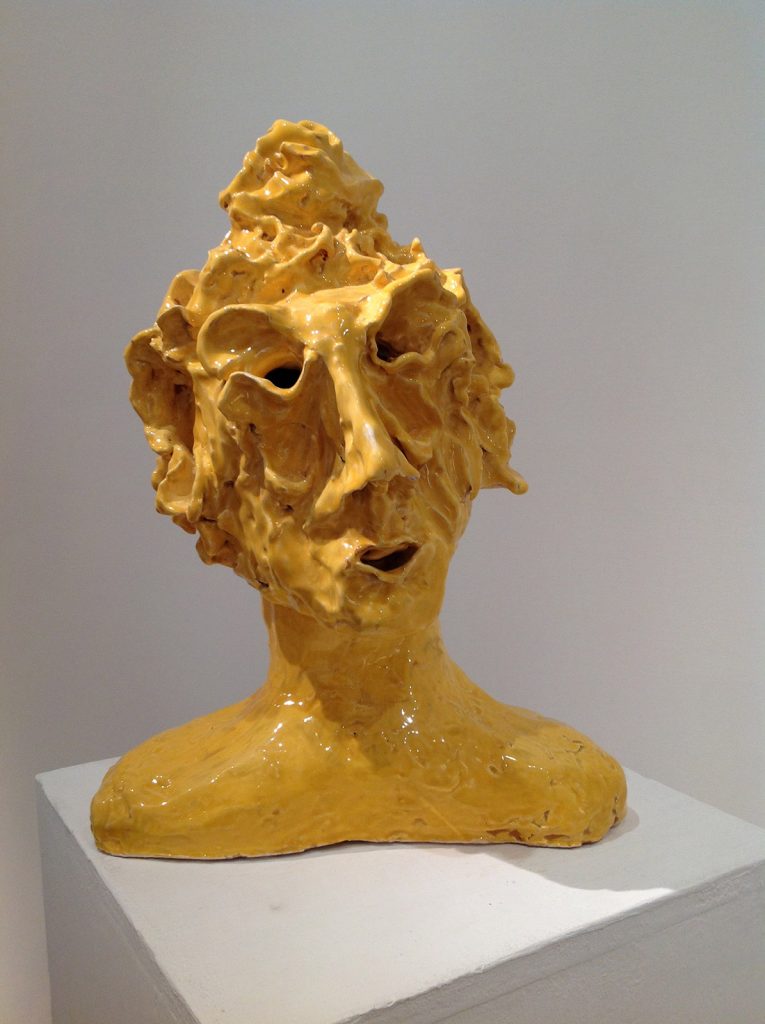

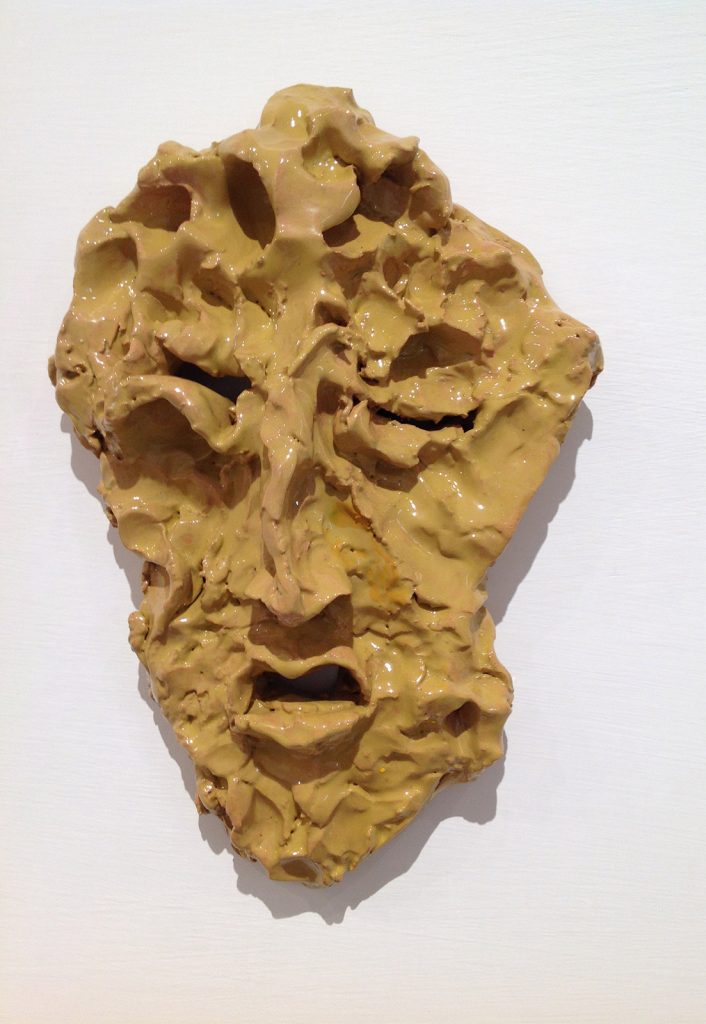

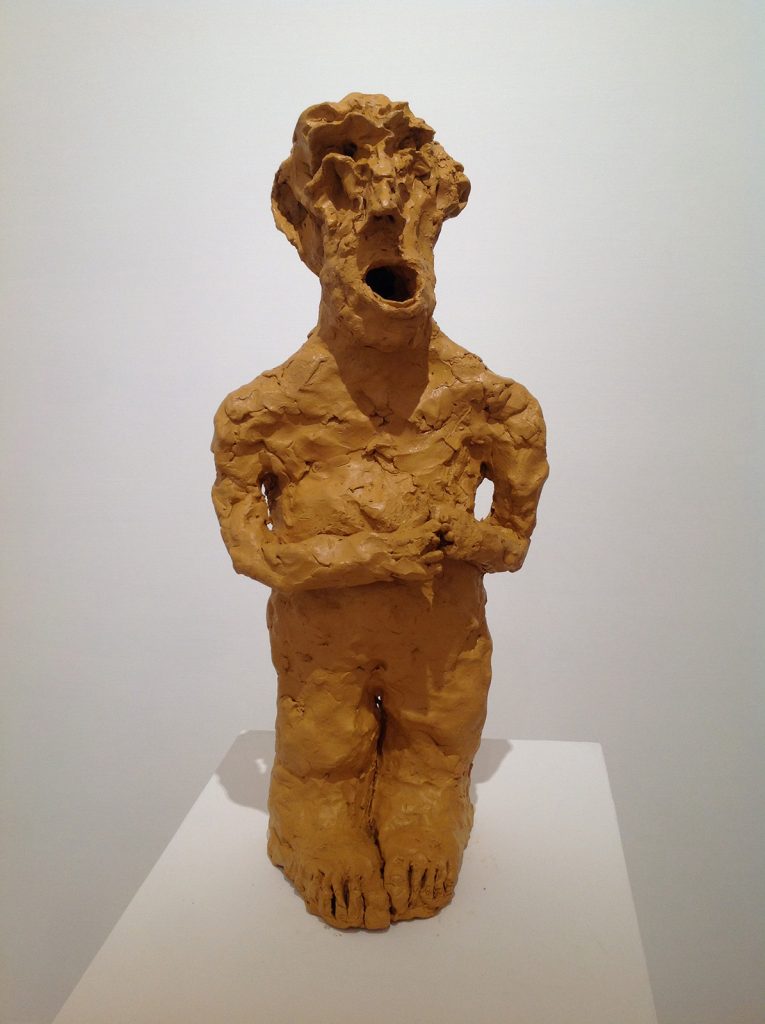

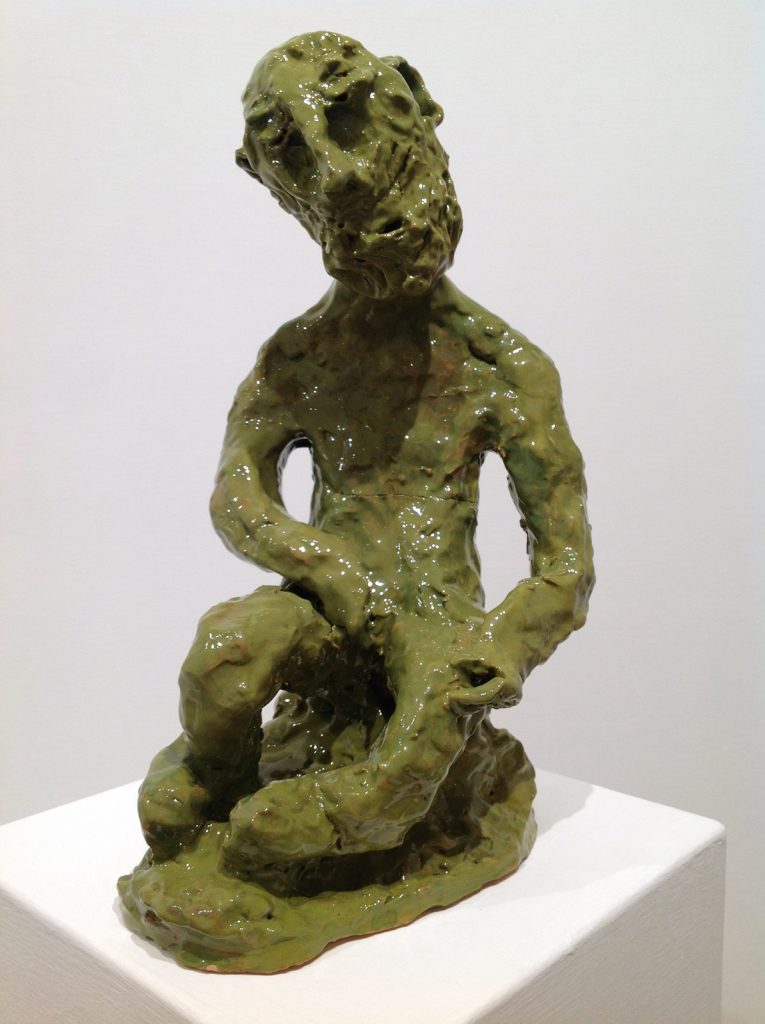

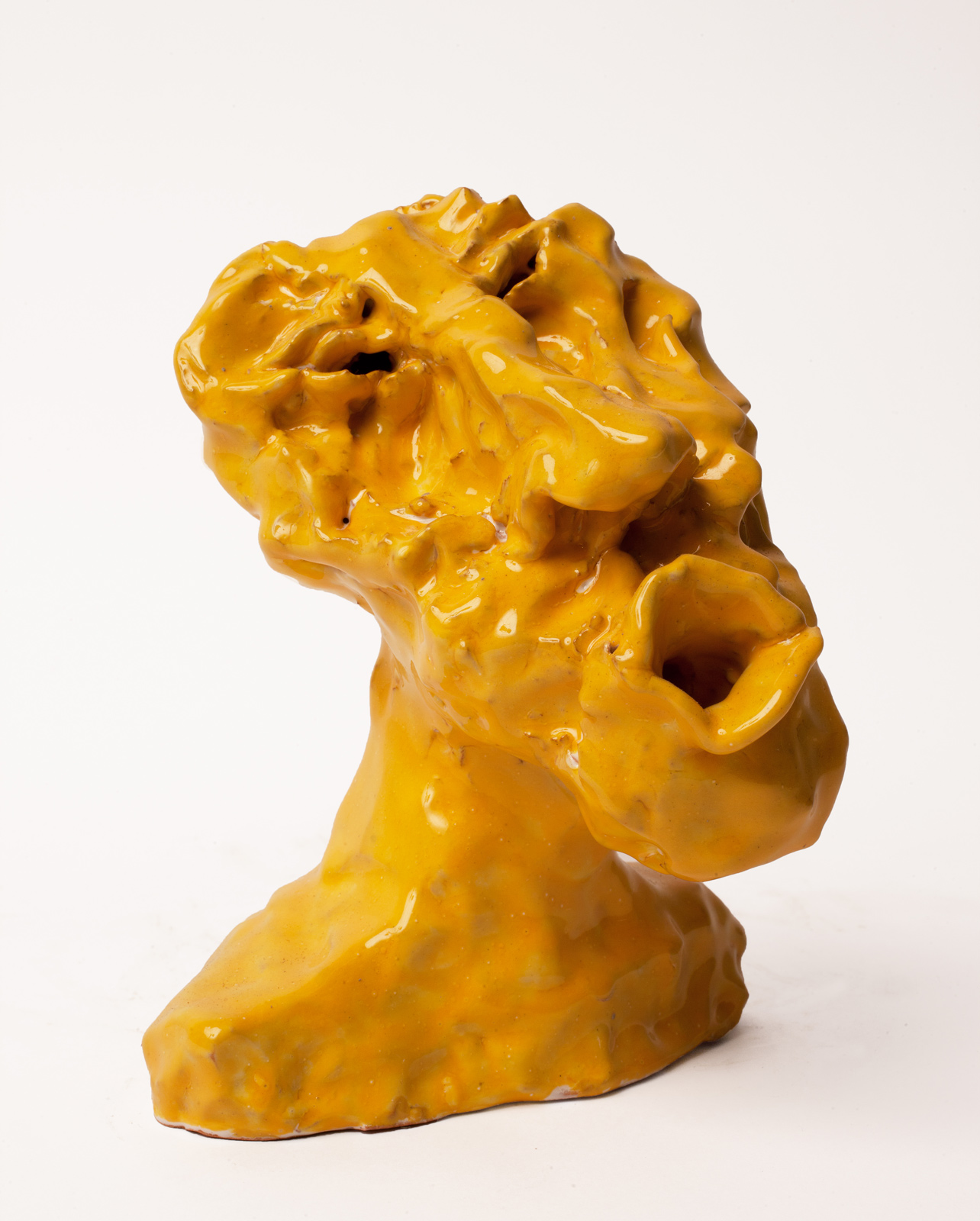

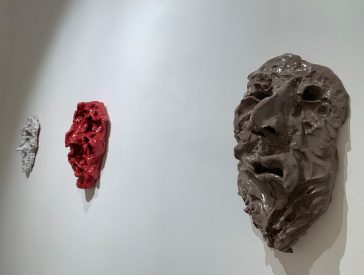

She says of her work: “If we can say that it is the narrative voice to generate imaginary forms in writing, then it follows that a form brings to life the narrative in sculpture. The order is flipped, but the outcome is analogous: both the written word and the carved form are bearers of worlds defined on their own terms. The worlds that emerge through my sculptures can be interpreted using a literary lens. They are Pirandellian Naked Masks; they echo the tragic-comedic paradoxes conceived by Gogol or a Kafkaesque estrangement. And yet – although they certainly do evoke the absurd and the paradoxes expressed in those worlds – they also exist in a confined dramatic space. Their bodies are shaped out of quasi-subhuman matter; dumb and incomplete beings, they try to find their reconciliation with the literate and relational reality of the world.”

The mouth is central to this work. “It is the creator; the tiny, concentrated Big Bang at the heart of each figurine,” quips Marco Di Capua in the catalogue.

“Suddenly, a crack in the clay becomes a gesture, a mark morphs into a sign, a cut turns into a wound, and, further, causes a grimace, revealing an individual existence, much like the crack that is our mouth does. Often I start there,” – the artist confesses – “the mouth is a medium for a creature that is craving the possibility to emit sounds and words. And just so, a persona emerges, most abruptly, stating a claim, and urging to break away from mere matter. I help him to do so quickly; I help him find his haven in matter and through matter.”

Di Capua also states, “There is something gentle, something archaic, in these small figurines that open their mouths as a makeshift Chorus, and let out silent chants or soft voices, that are never in vain. Theirs is not a desperate cry – like the distorted mouth on Edvard Munch’s bridge – nor does it resemble the cries that followed Munch’s like a violent echo, such as Francis Bacon’s caged papal faces. No, their cry recalls the mouth from Ernst Barlach’s Singing Man. Its peacefulness, its firmness, and the subtle irony that springs from the inevitability of an action that is performed in spite of everything. Why do you sing? Because I do!”

Where have these beings emerged from? Their maker calls them in turn her “little people”, her “army” or “the village”.

They yield to “diverse interpretations of their origin. To [Di Capua], they seem to have emerged from a liquid world, and to bear its print. They remind me of hardened lava (recalling Leoncillo or an early Fontana) or small, pointy rocks; perhaps a coral reef (for their chromatic splendor as well as the biomorphic branching of the figurines, which call one to my mind) composed of tiny elements that are silent allies and thus blend together easily, as fragments of a potentially infinite, sculpted lover’s discourse.”

The colors and titles are essential in qualifying each creature’s personality, as Di Capua also underscores, “So here they are, remarkable characters, actors playing a part. They introduce themselves; they are: The Blue Rider, the Shaman, the Boxer, The Man Who Laughs (from Victor Hugo) a highly counter-Michelangelesque King David, The Tenant (from Roman Polanski’s eponymous film) and a Pietà. Among them, we also find: the Accountant; the Judge; with reminiscences of Pirandello, but also of Gogol’s Dead Souls and, further, of some mysterious, telluric Spoon River…

Their broken physicality charges them with melancholy, rendering their bodies more fragile, and enhancing their personality by contrast. In it, they find the desire to be observed by viewers. And so, not any less imaginatively than Alberto Savinio would have said: narrate your story, you (little, big) people.“

Selected works

Gallery

Critical essay

Chorus

by Marco Di Capua

“I have not seen them in two days, and I already miss them,” Angela Maria Piga says as she walks me into her studio. I must say, I agree with her. When I first saw these sculptures some time ago, I felt as if I had been invited to take part in a celebration, one open to all – and hence also to me. They seem to evoke the loud noises of a lively encounter, filled with movement and joy. It is common to speak of sculpture as something that merely sits there, motionless, perhaps resembling a morsel of eternity and offering viewers a glimmer of transcendence, or a possible consolation for our inevitable mortality. I can think of nothing more distant from this description than these figurines. They stand opposite the complaint that came from Arturo Martini, the Italian 20th century sculptor, who lamented that sculpture was considered as dead as a Classical language. Nothing could be farthest from the truth, here, in Angela’s studio. Here, her sculptures squat about our feet in full force; they are confident, vibrant, feverish, beckoning, muttering. Here, their chatter is both sad and joyful, yet always deep, surfacing through their myriad gestures and colors. The crowd, the attack, the siege are the images that come to mind when confronted with this population of tiny people. They are accomplices, compact and prolific, like a small army easily encircling its viewers and asking to be heard.

Angela’s first exhibition as a sculptor comes under a poignant title, Haven. It concludes a year of work and research. The title captures this journey: the haven is the point of arrival and of safety. In the Italian original the title – Approdo – holds a powerfully symbolic and layered meaning. It means to reach the shore; to complete a journey with positive results. But the word finds its root in the German and ancient Scandinavian word for mouth. Angela writes this in a Whatsapp message that is filled with exclamation marks. She follows this by stating that she had a Swedish great-grandfather, Gustaf Kollerstrom, who was also a Theosophist, as if to underscore (although she does not need to) the quasi-metaphysical implications: a circle seeming to close, as circles sometimes do, unleashing undercurrents of meaning, fate, or destiny.

The sculptures, as the viewer can easily see, are filled with mouths. There are open mouths, thirsty mouths, crooked ones, ones distorted in a grimace, possibly expressing pain; there are mouths that seem to have something to say, or perhaps scream, or sing. Images that are painted or sculpted at times do so: with utter tenderness, they seem to make an effort to break out of their stillness and open their mouths to speak. We cannot hear the sounds they make except with our imagination. That said, no scream was ever as piercing or moving as the eponymous one captured by Edvard Munch on the bridge. That mouth is not the mouth that comes to mind in this occasion, though. There is something gentle, something archaic, in these small figurines that open their mouths as a makeshift Chorus, and let out silent chants or soft voices, that are never in vain. Theirs is not a desperate cry, nor does it resemble the cries that followed Munch’s like a violent echo, such as Francis Bacon’s caged papal faces. No, their cry recalls the mouth from Ernst Barlach’s Singing Man. Its peacefulness, its firmness, and the subtle irony that springs from the inevitability of an action that is performed in spite of everything. Why do you sing? Because I do!

The ‘mouth’ is central to this collection. It is the creator; the tiny, concentrated Big Bang at the heart of each figurine. “I always start from the mouth,” Angela quips. As she responds to my questions, I watch her trying to understand this small population of voicers more than she ventures to explain it. Carved from nothing, in turn they paved their way into the mind and hands of their creator, where they were invested of their colors. They moved forth in pairs or alone but always as part of a single procession. Where did they come from? What childhood memory, mythology, profound imaginative pool, or psychological well generated them? Which legends, Angela wittily asks, produced them in an attempt to become mundane, ordinary, and domestic? Which wood filled with glistening moss, tree trunks, and animated barks produced them? How can we learn from their world, a world of gnomes, where they can morph, change their form, camouflage. Which polychrome cave let them out, engraving on them a fantastic memory of their origin?

Their magical presence will evoke thoughts and impressions that are different for each viewer, leading to diverse interpretations of their origin. To me, they seem to have emerged from a liquid world, and to bear its print. They remind me of hardened lava (recalling Leoncillo or an early Fontana) or small, pointy rocks; perhaps a coral reef (for their chromatic splendor as well as the biomorphic branching of the figurines, which call one to my mind) composed of tiny elements that are silent allies and thus blend together easily, as fragments of a potentially infinite, sculpted lover’s discourse. Stylistically, through every straight line and every regular shape, an anti-classical approach triumphs, allowing graceless beauty to emerge from irregularities and crumpled, wrinkled forms, in an attempt to reduce formal calculations to nothing. The shapes are existentially and irregularly moulded.

I have started calling the figurines little characters (they are veritable actors, as I will explain later) that, gifted with both a ‘high’ and a ‘low’ dimension can cross highly different points of view and are always complementary in size. You can observe them from above, crouching on the ground, in intimate communion with the floor, or placed far above the latter, boldly face-to-face with you, imposing their urgency on you, as if you were one of them. But I wanted to address something yet different; the size of these ceramics, these “lapsed giants,” as Angela lovingly calls them, seems to recall thoughts expressed recently by Hervé Clerc in his powerful book Dieu Par la Face Nord, (Albin Michel, 2016; literally: God reached from the Northern Side; as of yet, untranslated in English, translator’s note). Here, the Franco-Swiss intellectual claims that the mystical experience, teaches that a single day can be charged “with the immensity of the Milky Way, while the following is as small as a ladybug.” “Similarly art,” he continues, “can first grow and subsequently shrink to the point of becoming invisible, or almost invisible. A brief anecdote from 1945 will illustrate this idea further. Giacometti, who was then in Switzerland – his home country and the place where he spent the years of the war – was preparing his return to Paris. The publisher Albert Skira asked him: ‘How will you be able to take all your sculptures?’ Giacometti took a matchbox out of his pocket and opened it, showing its content to Skira. Inside were three or four figurines the size of a needle. He carried everything he needed in his pocket.”

So here they are, remarkable characters, actors playing a part. They introduce themselves; they are: The Blue Rider, the Shaman, the Boxer, The Man Who Laughs (from Victor Hugo) a highly counter-Michelangelesque King David, The Tenant (from Roman Polanski’s eponymous film) and a Pietà. Among them, we also find: the Accountant; the Judge; with reminiscences of Pirandello, but also of Gogol’s Dead Souls and, further, of some mysterious, telluric Spoon River…

Aware of their own theatricality, they perform and pretend, miming narratives, while a few of Angela’s paintings morph into an exotic backdrop. I say this as I am observing The Guest’s dangling leg or Achilles as he looks at his missing limb befuddled. It was not necessary for time – described by Marguerite Yourcenar as an unforgiving sculptor – to unleash its destructive winds onto these figurines; nor have they had to encounter traumatic wars or natural disasters; nor yet have they had to be submerged by sea or sand, for them to relinquish parts of their physicality and thus paradoxically gain meaning from an emptiness, or an anatomical incompleteness. Their broken physicality charges them with melancholy, rendering their bodies more fragile, and enhancing their personality by contrast. In it, they find the desire to be observed by viewers. And so, not any less imaginatively than Alberto Savinio would have said: narrate your story, you (little, big) people.

Extras

Exhibited Artists