Maja Arte Contemporanea is delighted to present the first solo exhibit by young Molisian artist Anna Di Paola.

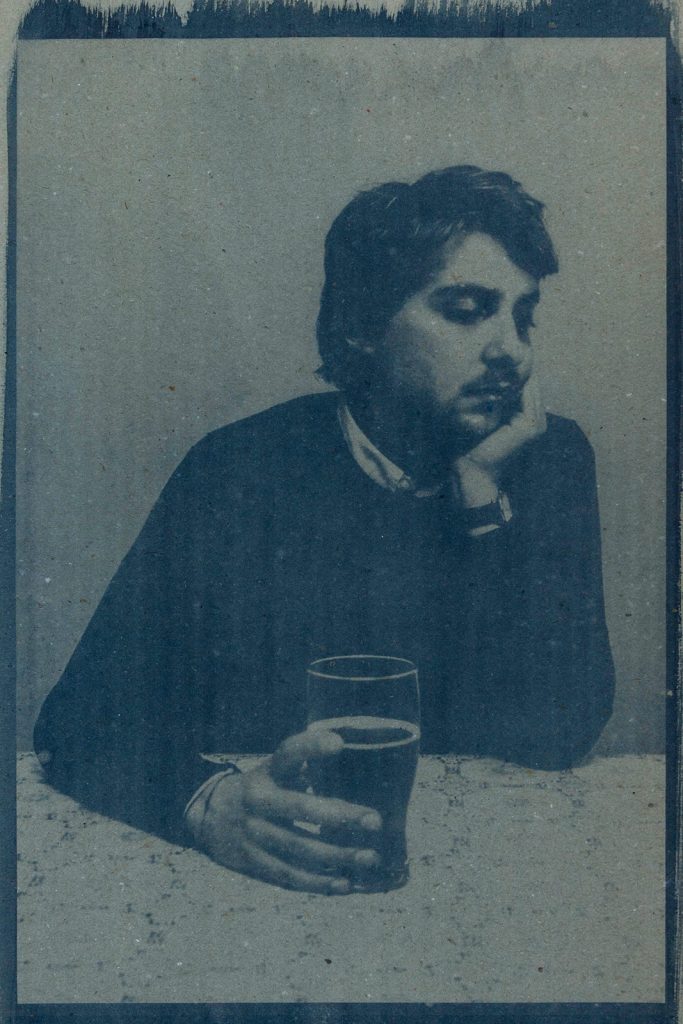

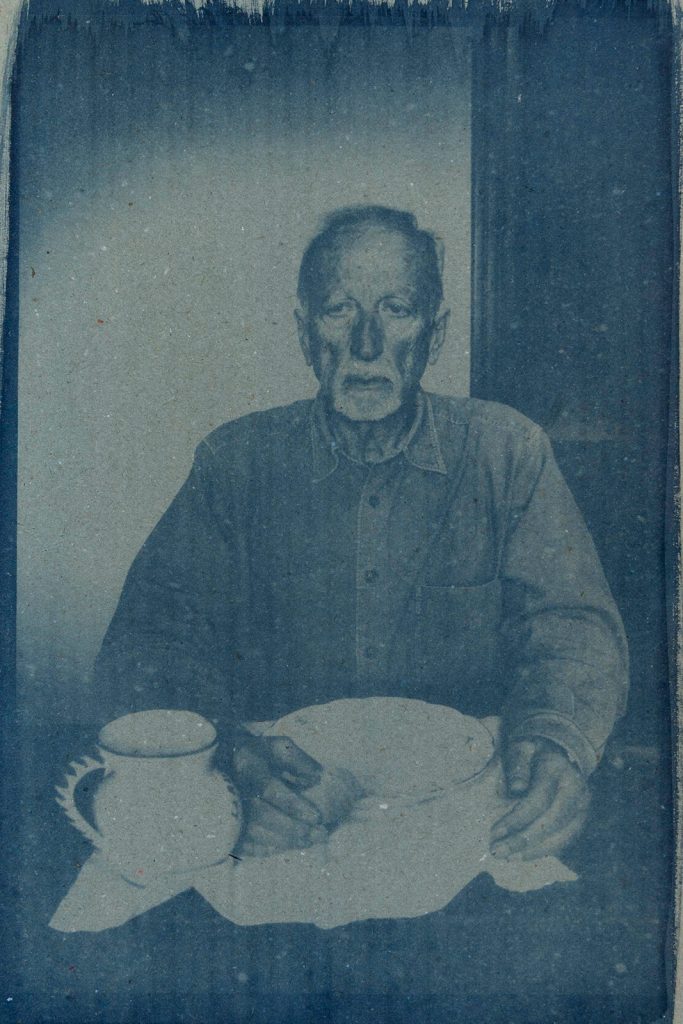

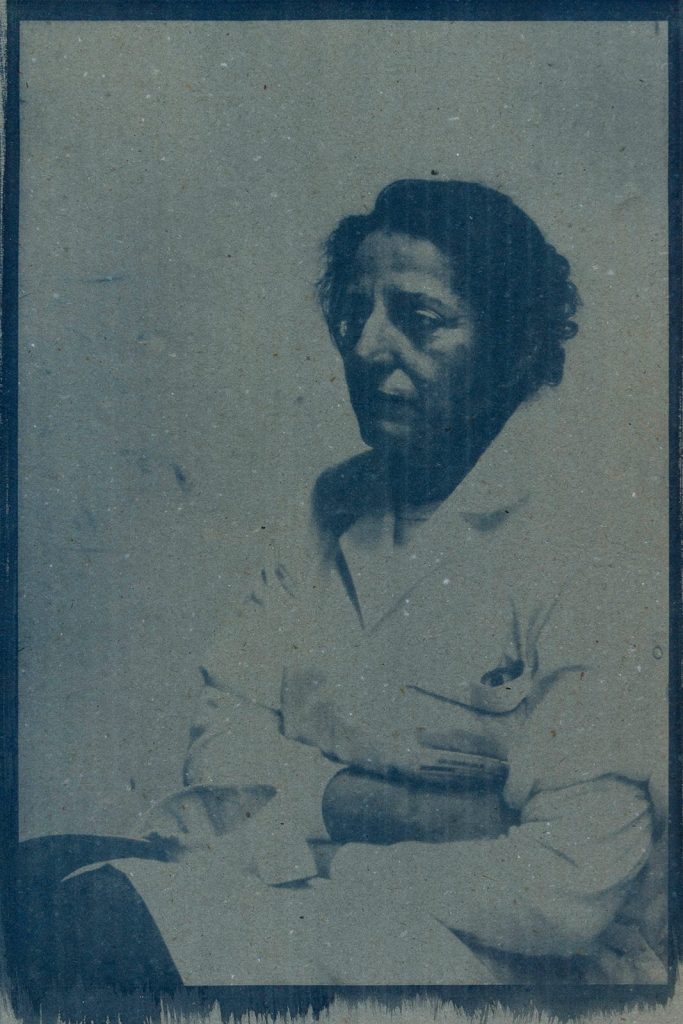

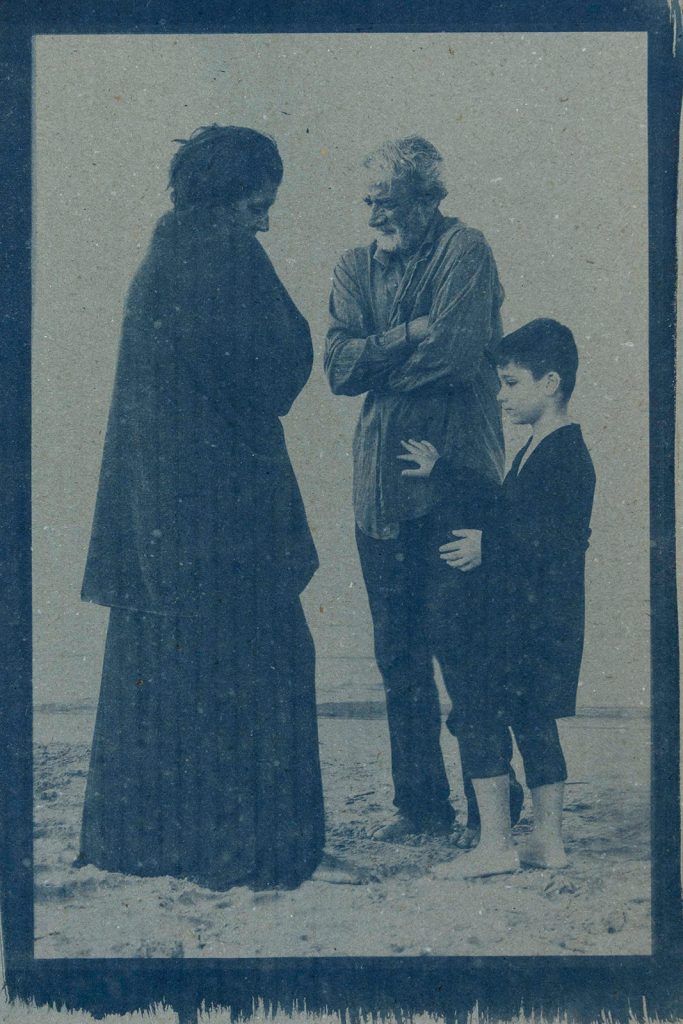

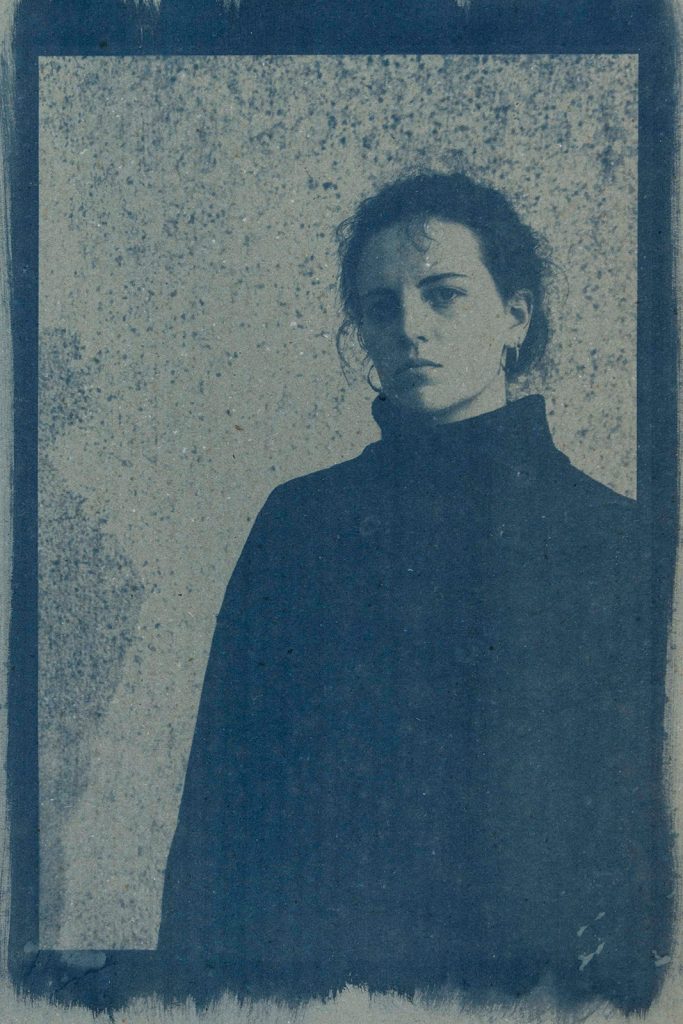

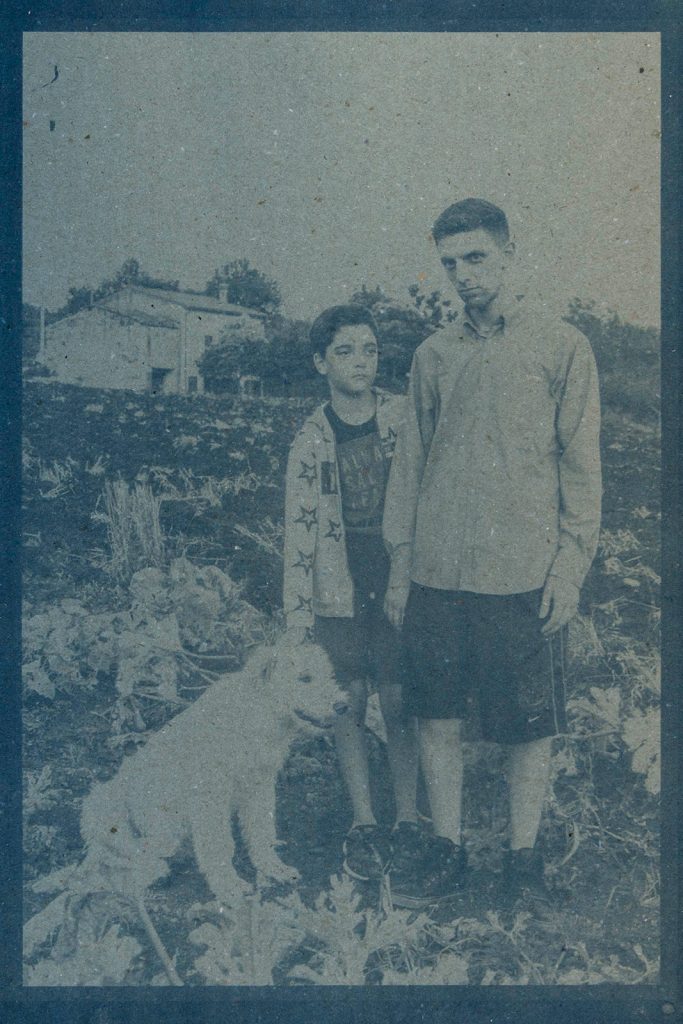

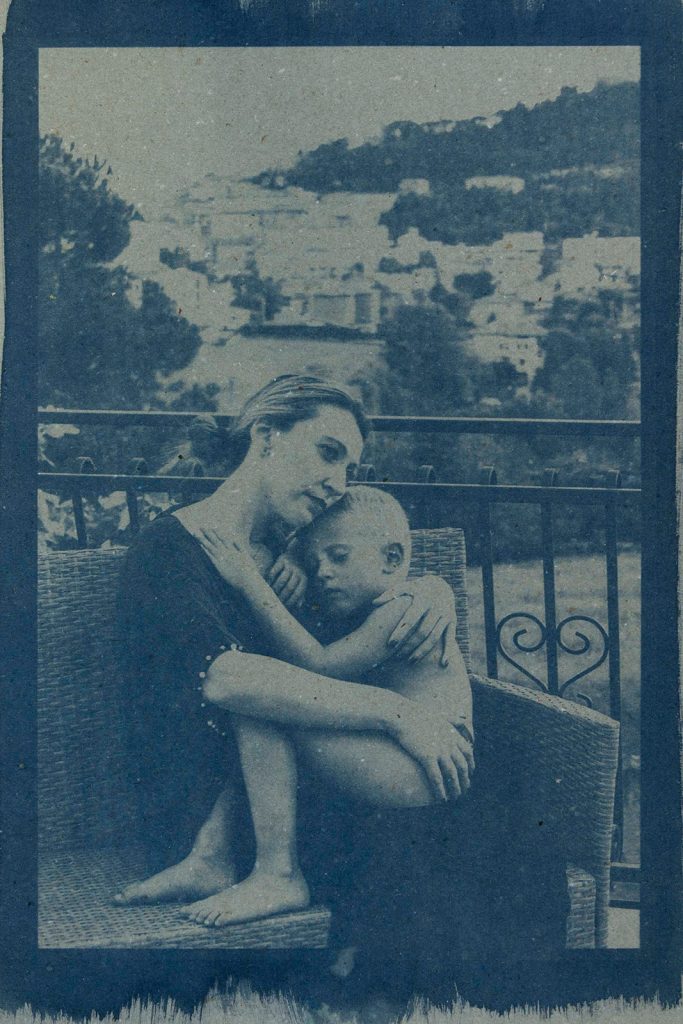

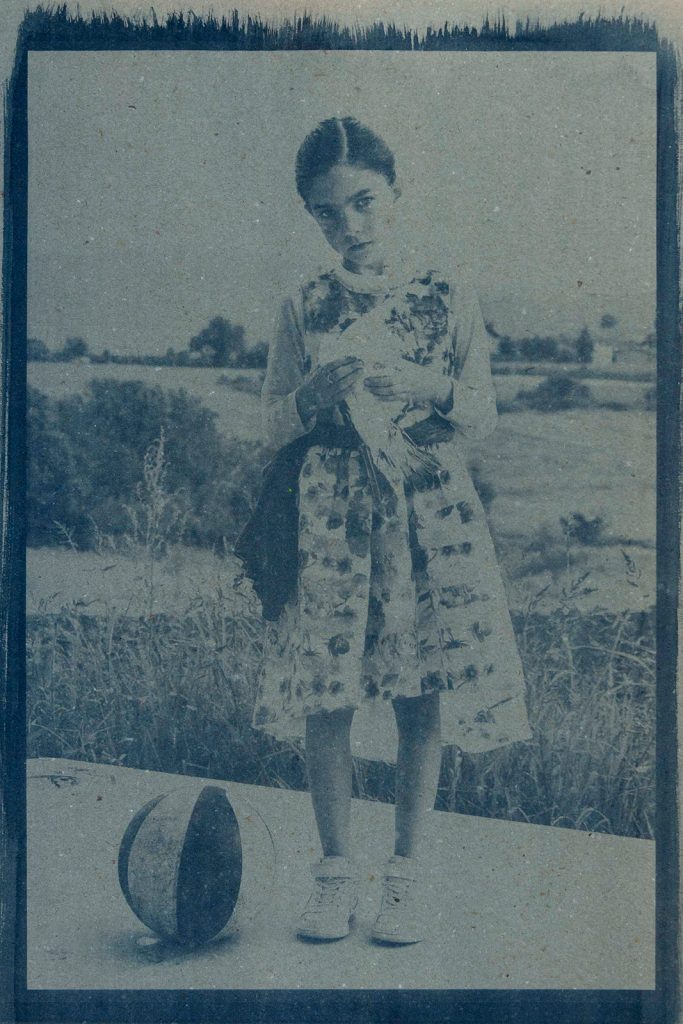

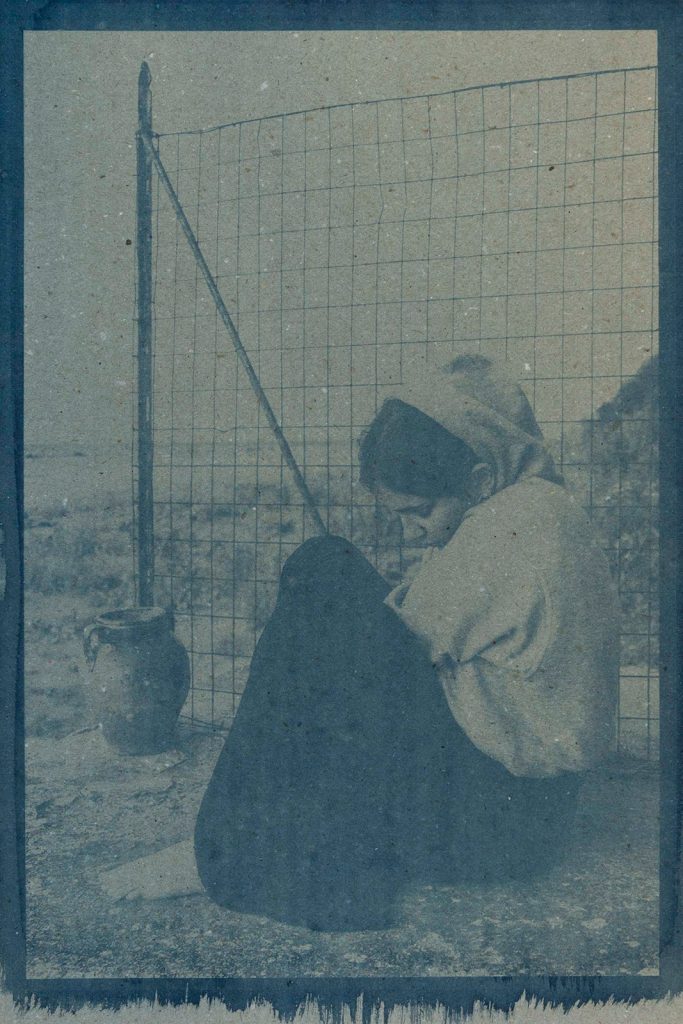

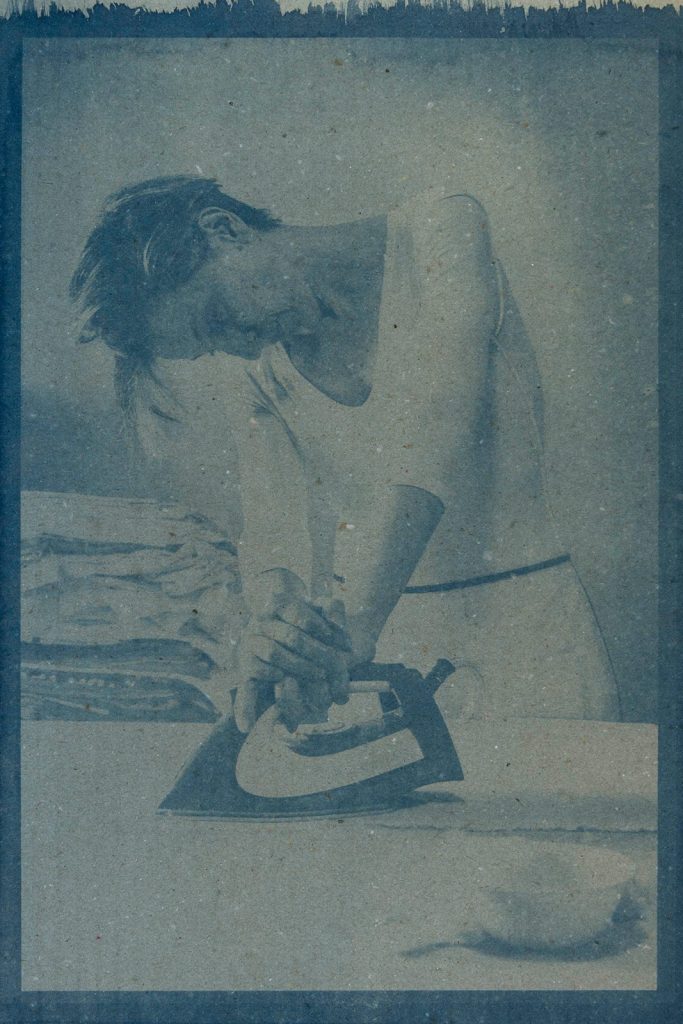

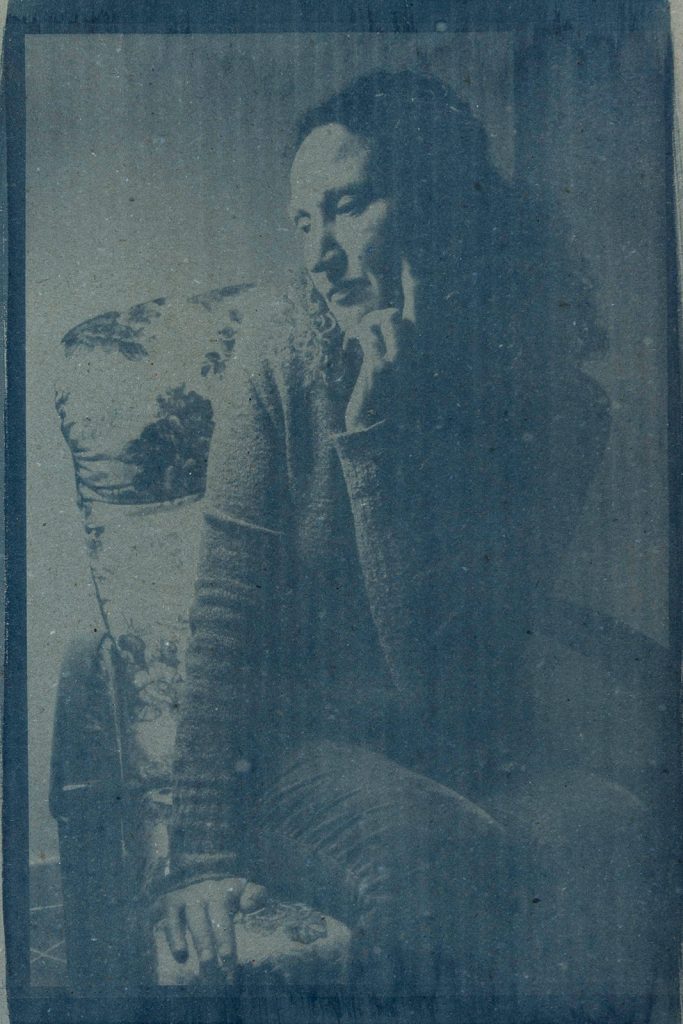

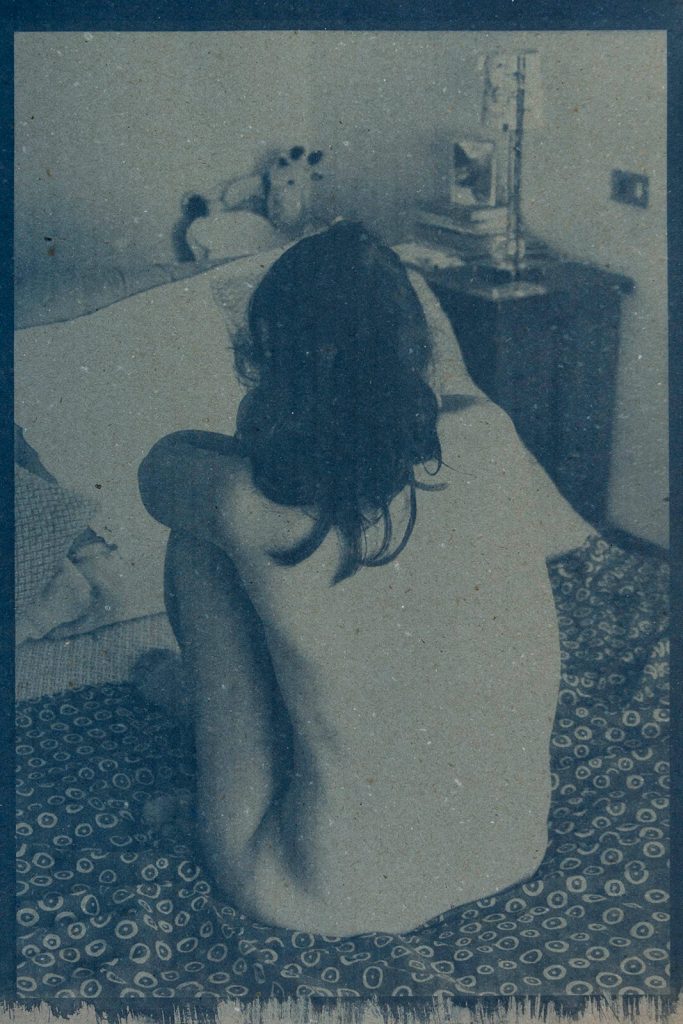

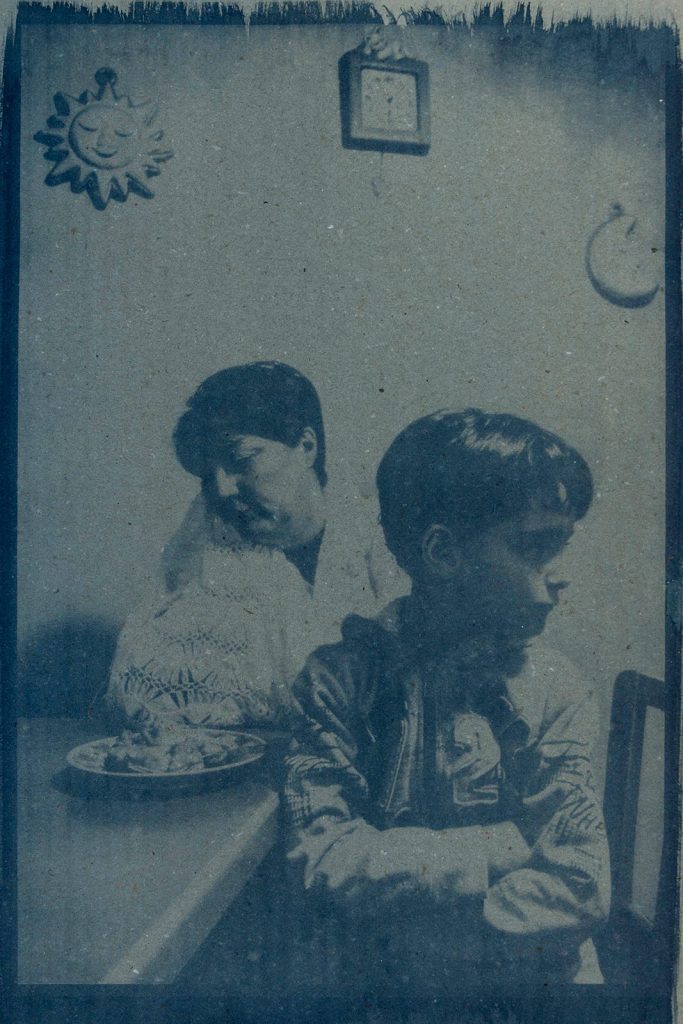

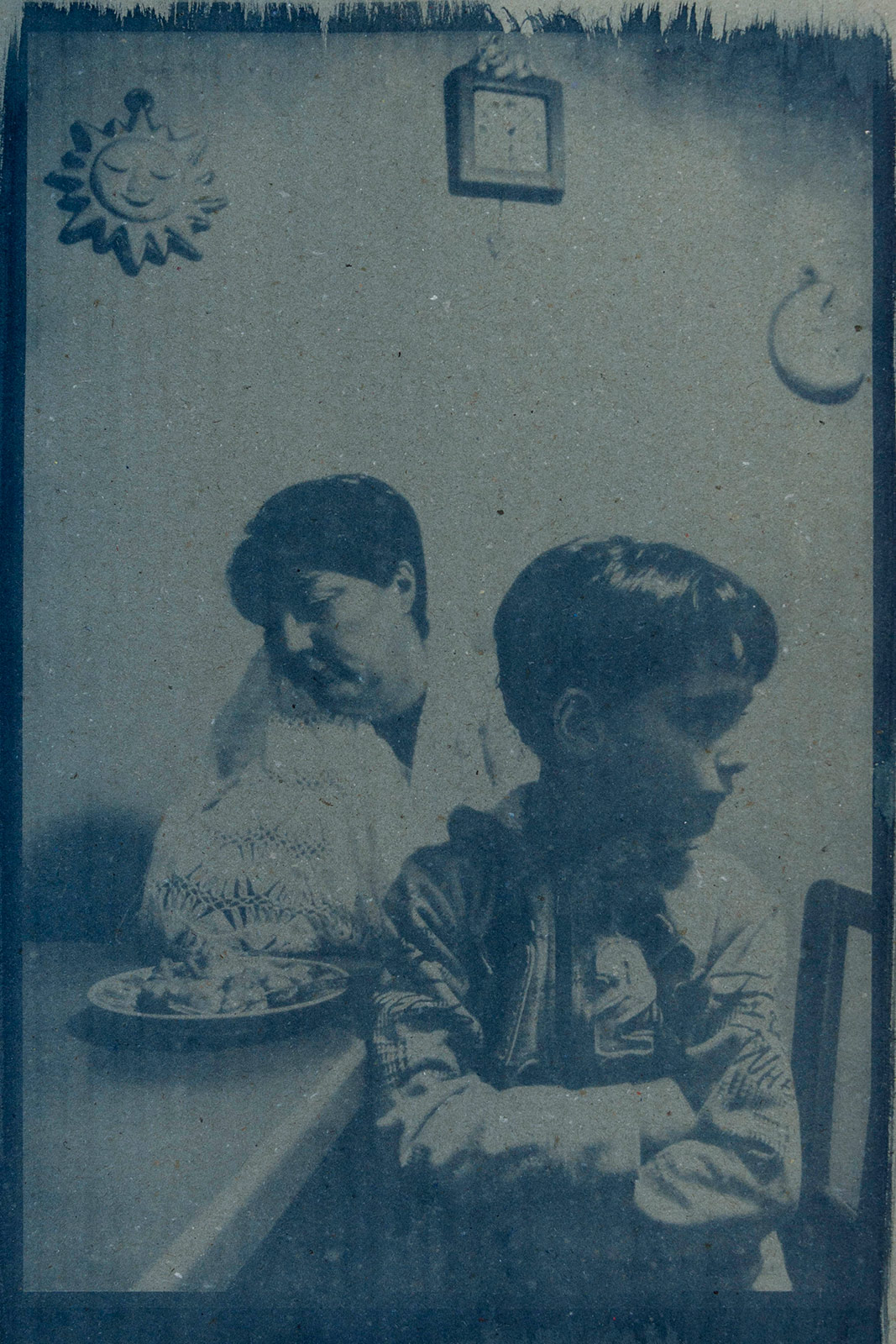

Di Paola uses cyanotype to make fifteen portraits emerge out of a Prussian blue print; through these she evokes fifteen analogous images from Picasso’s Blue Period.

“Choosing to initiate a dialogue with Pablo Picasso is a bold and brave act on behalf of any young artist: the latter runs the risk of being crushed under the weight of the master’s unparalleled celebrity or to fall prey to the conventional vices of Picassisms, so common in the 1950’s. And yet, Anna Di Paola dared do so and conquered the challenge she set for herself”, Canova comments in the critical text found in the catalogue.

Orietta, Agostino, Paolo, Chiara, Gianmario, Emanuela, … Anna, are the timeless figures caught in these enigmatic “Molisian portraits.”:

“Surfacing out of oblivion, those faces are still fixed in the pose wanted by Picasso, but a subtle, ineffable vibration moves through the cracks of the paper they are caught on. Still shielding themselves from the cold, ironing, closed in the prison cells of their melancholy, hugging their children or caressing doves or puppies those people linger on. And all of this seems to occur during an eve without nightfall, illuminated by a light deprived of the day’s sun and which will never succumb to darkness. In this perennial dusk, made of an immaterial substance which is both meagre and marvellous, Di Paola’s shots enter into their hermetic dialogue with the master’s art. Through it, they find an affinity of images and feelings which culminates in the secret reflection of Picasso’s solemn and suffering self-portrait caught through Di Paola’s eye. This dialogue guides the viewer through the light and melancholy journey offered by the photographs, reviving their mysterious pictorial nature of the latter.”

Selected works

Gallery

Critical essay

Feeling blue

by Lorenzo Canova

Choosing to initiate a dialogue with Pablo Picasso is a bold and brave act on behalf of any young artist: the latter runs the risk of being crushed under the weight of the master’s unparalleled celebrity or to fall prey to the conventional vices of Picassisms, so common in the 1950’s. And yet, Anna Di Paola dared do so and conquered the challenge she set for herself. Her work is not driven by Picasso’s immense contribution to the history of art; it rather stems from the mystical aura which surrounds his remarkable talent as clouds gently gathering around the highest mountaintops.

The conversation she has with the master’s works — intended as a veritable tribute — is inspired by Picasso’s Blue Period. The figures are bent by an irredeemable, timeless grief; imbued with melancholy, Picasso’s images elevate and immortalise the fate of those marginalised and ignored by both society and the world at large. It is a desolate landscape, peopled only with beggars, alcoholics, street artists and human beings whose extreme poverty seems almost ancestral.

Di Paola’s approach to Picasso is intelligent. It resembles a style popular between the end of the 1970’s and the beginning of the 1980’s when painters, sculptors, performers, concept artists, videographers and film and theatre directors all used citations to develop their projects. This was the case, for example, for Gina Marotta’s development of the set for Carmelo Bene’s Hommelette for Hamlet in 1987; interestingly, Marotta is originally from Molise, also Di Paola’s home region.

In Di Paola’s case, she does not merely cite the old masters or early modern art, as was a common stylistic choice a few years back (and as is still the case for Jeff Koons, to name one example). Her journey backwards digs deep, searching for the very roots of modernity through one of its most noble fathers. To do so, she chooses Picasso’s most intimate phase, a preparatory period which launched the master forward by setting the stage for what was to come: his most innovative works, the ones that would change the course of art history.

Through her photographs, Di Paola aims to evoke many of the paintings from Picasso’s Blue Period. Photography is her preferred medium and one she has mastered fully. She captures images of ordinary people, often selected for their uncanny resemblance to Picasso’s subjects, and she has them pose without a staged set. Her shots are rendered particularly interesting by her choice of printing paper. Di Paola came across the old paper almost by chance; she then chose to use cyanotype printing to recreate the monochromatism characteristic of Picasso’s work during the Blue Period. The visual impact of her images simultaneously nods to the past and looks ahead to more contemporary works.

The series’ title — “Misero Blu” (Blue Misery) — renders with graceful precision the feeling that emerges from the destitute circumstances portrayed in Picasso’s works. The conversation with the latter is explicit and yet acknowledges that the pictures are a retelling and not a mere citation of the master’s works.

In a certain way, Di Paola seems to slip behind the past century’s curtain so as to find the faces of the very people that Picasso portrayed in his works. She gives those faces and souls new life; and yet this life remains suspended in an azure limbo, an intermediate space where time has slowed down almost to a standstill. Surfacing out of oblivion, those faces are still fixed in the pose wanted by Picasso, but a subtle, ineffable vibration moves through the cracks of the paper they are caught on.

Still shielding themselves from the cold, ironing, closed in the prison cells of their melancholy, hugging their children or caressing doves or puppies those people linger on. And all of this seems to occur during an eve without nightfall, illuminated by a light deprived of the day’s sun and which will never succumb to darkness.

In this perennial dusk, made of an immaterial substance which is both meagre and marvellous, Di Paola’s shots enter into their hermetic dialogue with the master’s art. Through it, they find an affinity of images and feelings which culminates in the secret reflection of Picasso’s solemn and suffering self-portrait caught through Di Paola’s eye. This dialogue guides the viewer through the light and melancholy journey offered by the photographs, reviving their mysterious pictorial nature of the latter.