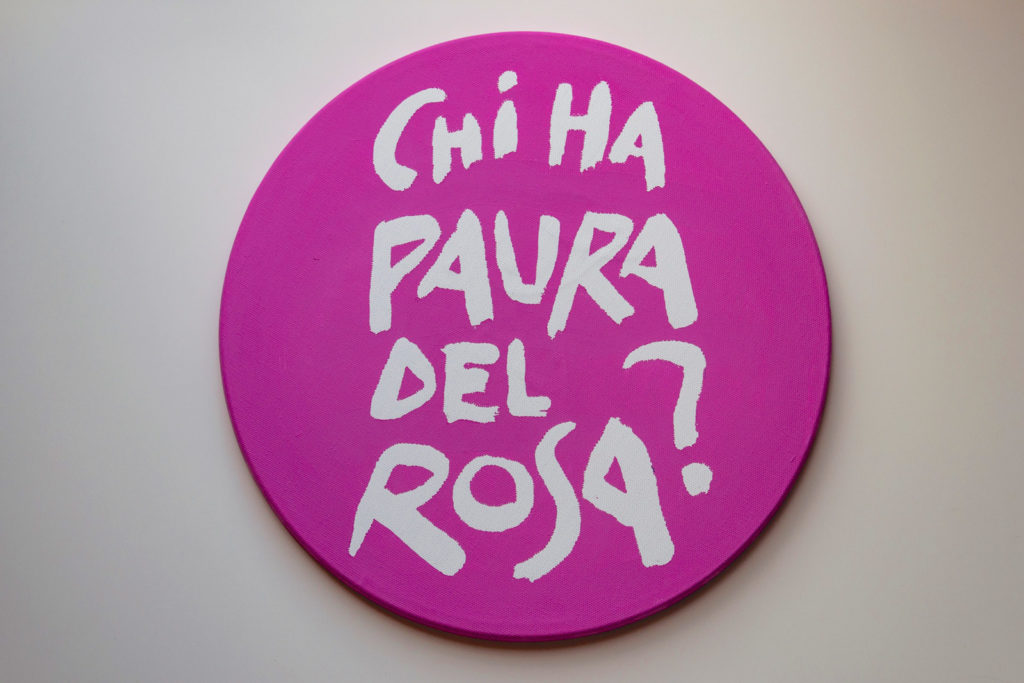

Maja Arte Contemporanea is delighted to announce Ria Lussi’s personal exhibit, “Chi ha paura del Rosa?” (Who is Afraid of Pink?).

On display is a collection of ironic and playful self-portraits; it was inspired by Daina Maja Titonel’s invitation to close a two-year cycle of exhibitions dedicated to female artists. Lussi responds by challenging the current gender disparity through permutations of her “Rose”. Completed in acrylic paint on a round-shaped canvas, each portrait attributes an adjective to its “Rose”; in turn, this becomes an interpretive lens colouring the candid and metamorphic figure that emerges. Lussi’s sophisticated research into chromatic variations renders each of her roses unique.

The exhibition is completed by a bust of Leonardo da Vinci in Murano Crystal (2016); three Rosaries (2016) in blown glass by Maestro vetraio Silvano Signoretto, and the excruciating “face” of Irene (2014), the only empress to have ruled in the fifteen-century history of the Roman Empire.

The reflection that emerges is a shared and striking concern with the gender gap. This is compounded by the gallerist’s own research: she used her expertise as a mathematician to develop a comparative statistical analysis of the state of the gender gap in the visual arts.

To cite only some recent data:

– Between 2008 and the first five months of 2019 over $196,6 billion has been spent on art at auctions. Only 2% of this sum was designated to works produced by female artists ($4 billion for close to 6000 artists). In the same timeframe, Pablo Picasso’s works alone were auctioned for $4.8 billion, a staggering contrast.

– The record auction sale for the work of a female artist (the painting “Propped” by Jenny Saville) is $12.4 billion (Sotheby’s, October 2018) compared to the $ 91,1 billion spent for “Rabbit” by Jeff Koons (Christie’s, May 2019).

Responding to a pressing desire to take action and make a contribution towards a change, the Gallery’s website includes a section dedicated to the topic. Its name is inspired by this exhibition.

The exhibit is corroborated by a catalogue including critical essays by Umberto Palestini, Gloria Fossi and by a botanical note on roses by Roberto Valenti.

Selected works

Gallery

Critical essay

Fashioned in a circle

By Umberto Palestini

Who is afraid of pink? One question. Maybe a challenge? A claim?

I have some doubts. If I think of Ria Lussi’s research, I would never be able to confine her to a gender context and perhaps she herself would be horrified at the very thought that someone would force her into the rigid meshes in an expressive vein, albeit laudable and just. Her art has always directed its aim towards the search for a totality in which the female universe has always been a founding element, but not the only one, of a cosmogony that tends to embrace the entire universe. For this reason, the evocation of pink does not take me back to a colour, which in her recent work is in any case the star, but to the flower and the passion it embodies. We think of the blood of Aphrodite left on the thorns of the brambles to save the beloved Adonis which turns into roses. The idea that death is defeated by love seems to me more in keeping with her creative model in which rebirth, preserving forgotten or distant figures, bringing them back to a new life, is a modus operandi.

Today Ria Lussi asks us a question that is also an exhortation not to dodge questions and she does this with a series of circular works, which we know refer to perfection and cyclical time. On the surface of the circular works, in her very personal way, she creates a series of self-portraits, detailed figures poised between irony, haughtiness and subtle enchantment, even going as far as touching on eroticism with The Playful Rose, in a refined manner.

Part of the works unfolds on opaque backgrounds, with a powdered effect created with acrylic, where the vibrato is provided by the different shades of pink that get brighter and brighter until they become deep purple or shocking pink. In others, and this seems to me to represent the most interesting new aspect, the circular works are enhanced by thick, caressing brushstrokes that, in some cases, render the self-portraits not entirely evident, as if they were deliberately hidden, giving them a new perspective composed of precious tiles as in glittering mosaics and mother-of-pearl medallions.

Ria Lussi’s new works are repeated like a mantra and bring to mind a famous verse by Gertrude Stein contained in the poem Sacred Emily, “A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”.

In a lecture, Stein said about the verse: “And then later made that into a ring I made poetry and what did I do I caressed completely caressed and addressed a noun.”

Ria’s self-portraits, fashioned in a circle, manage to include myth and avant-garde, they become poetry and caress as in Stein’s poem, which contains a memorable phrase, the subject of attention and distinguished studies, such as the one by Umberto Eco: The Absent structure. The semiologist asks himself a question: “What do I understand of what Stein is saying to me? She only says ‘rose’, and leaves me free to fill that word with meanings that most belong to me and feel close to me. She calls into question reading, feelings and conjectures. She calls me into question.”

Eco’s reflection perfectly covers Ria Lussi’s work in its structured complexity; the research of an artist who has nourished herself with studies, readings, who offered the observer the freedom to interpret and gave feelings and conjectures by directly involving them, calling them into question.

Yes. Ria Lussi calls us into question. Who is afraid of pink?

Antique pink, modern pink, freedom pink

By Gloria Fossi

Who is afraid of pink? The title chosen by Ria is in question form, and presupposes, in my opinion, personal answers. I will say then, first of all, not to fear pink, God forbid. Nor do I recall ever having identified this colour with the female gender (this was not done in past centuries, at least in the figurative arts, as I will later mention). Nor do I suffer from phobias about other colours. I love them all, although I prefer shades of orange, yellow and pink: cherry pink, Tiepolo pink, powder pink, violet-pink.

Since the 14th century, pink has been a frequent colour in Tuscan, Florentine and Sienese painting (as well as in the north, such as the 15th-century Mantegna of Paduan origin). I have no intention of touching on ecphrastic values, symbolic or semantic meanings of this colour in art here, as the issue cannot be addressed in a few lines. However, pink was often used by the great masters, and in a sublime way.

I could cite an infinite number of examples, but here it is enough to recall some of the most famous works of the early fourteenth century, such as the admirable pink, almost transparent robe of the baby Jesus in the Maestà by Giotto in the Uffizi or the tunics of the saints in Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s paintings. Illustrious examples of the early 15th century are the synthetic, earthy robes of the apostles in the Florentine frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel in the Carmine, or the light pink of two gentle angels in the oldest known, yet enchanting, work by Masaccio: the Triptych of Saint Juvenal, in the Cascia Museum near Reggello, south of Florence. The faces of those two teenagers are not without identity, or rather, as I happened to call them, profil perdu, an expression dear to authors closer to us such as Théophile Gautier or Henry James.

Why are angels pink? Was it because angels were the first to ignore gender differences?

Then there are the pink buildings of the fifteenth century and early Mannerism (for example, the architectures of classical ancestry by Domenico Veneziano are pink. And then, there is the metaphysical, cold pink of the ethereal young man depicted by Pontormo in the Capponi chapel in Santa Felicita in Florence. His skin is a magnetic and surprising colour.

Skipping endless passages, we come to the unsurpassed pinks of Tiepolo’s skies: dazzling light, and below figures of an “unhindered, effortless fluidity” that ascend “to all the heavens, without forgetting the earth”, as Roberto Calasso wrote in his Il rosa Tiepolo, where he also evoked the Albertine of La Recherche.

Taking a prodigious leap forward, one of the most intense works that stands out by Lucio Fontana is the pink series of the Nineteen Sixties. And just a few months ago – forgive me for making a slightly blasphemous comparison – I couldn’t help remembering the pink T-shirt (and cap) worn on the tennis courts by the legendary Roger Federer.

In retrospect, years ago, I travelled the spectacular Overseas Highway south of Florida with a pink scooter and a matching hat. Why did I choose that colour, among the many that were offered to me in the rental shop? Perhaps because, in a play of contrasts, it blended so well with the intense blue of the sea, almost flush with the paved road linking Miami to Hemingway’s iconic Key West, thirty miles in the face of Cuba. Or rather, because it gave me the sense of what was to be the first of many trips purposely made alone? Pink as a taste of freedom. Leonardo – I mean Leonardo da Vinci – admonished his pupil: “If you are alone, you will be all your own“, even though he often contradicted this statement, as well as many others of his, at the court of the powerful with affable nonchalance. Even Leonardo loved to wear a very elegant pink jacket. He was not the only one, in the 16th century: among the most remarkable examples is the Bergamasque knight Gian Gerolamo Grumelli, portrayed full-length as a king of Spain, dressed entirely in coral pink, including socks and shoes: that is how he was depicted again in the 1560 portrait by Giovanni Battista Moroni. Both, the painter and the client, evidently did not fear pink; on the contrary, they were proud of it.

And then, one cannot ignore the primary meaning of the term ‘rose’, the botanical one. Close to home, I have friends with a nursery of old roses, who taught me how to grow them. This helped me to study them in Botticelli’s paintings, and to try to identify the species present, especially the pale pink ones that swirl in The Birth of Venus and fill Flora’s robe in Primavera. Roses, by far, stand out among the many other colourful species depicted by the painter loved by the Medici.

Obviously, artists have also loved other colours – think of Cézanne’s ‘Naples yellow’ or Matisse’s Fakarava blue, named after an atoll in the Tuamotu archipelago in Polynesia, which the great French master visited in 1930, almost as a gamble (but also dear to Melville, Jack London, Stevenson, and lastly Simenon). It is all too obvious to recall the oranges and chrome yellow used in the late 19th century by Gauguin and van Gogh.

Now I am curious to see the pinks of Ria/Rosaria, which I think is a beautiful name. Among other things.