“To see him attached in this way to the animal, whose form was gradually inflated, while he seemed silently to grow thinner and thinner as he emptied himself of his breath recalled some strange sort of metamorphosis whereby a man is changed into a beast.” (trans. Frances Frenaye)

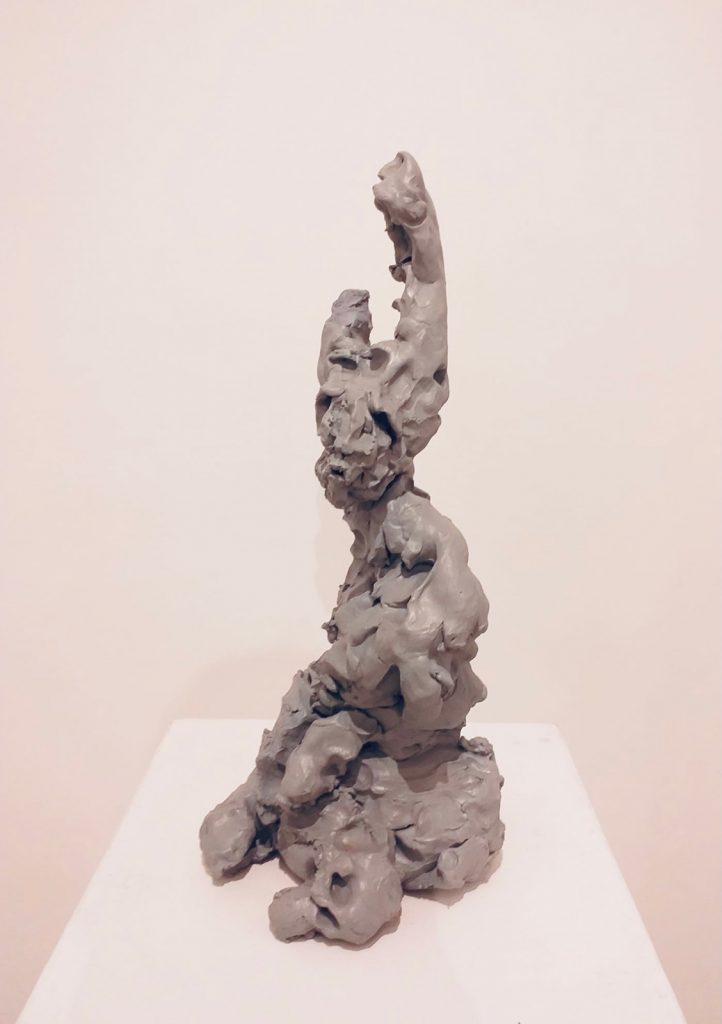

Taken from Christ Stopped at Eboli, these words by Carlo Levi’s (1902-1975) crystallise an anthropomorphic liminal world, one lying between the animal and the human. It is to this world that Piga’s 25 sculptures (ceramic and terracotta) belong.

In a time characterised by new frontiers: the birth of lab chimeras and the emergence of anthropological hybrids; the co-existence of artificial and natural intelligence; the rise of new forms in all domains, the sculptures serve as a metaphorical lens. They convey a blown up image of such destabilising changes, which are relevant in both individual and sociological terms, allowing the viewer to reflect upon the new and unsettling adaptations that these demand of humankind. The synecdoche, in this case, refers to the part of a whole that is inherently void.

The lunar rabbit Yuètù dominates the “anthropomorphic animals”; he originates in China in the IV BCE, and is also known as the golden rabbit. In the Buddhist Jakata tales, the rabbit is rewarded for his generosity by the deity Śakra, who inscribes his silhouette on the moon so that he may be remembered by all. In the Chinese version of the legend, it is the goddess of the moon Chang’è to take him to her satellite. Once there, Yuètù steps on the elixir of life. The rabbit’s legend still lingers in Asia where, when the night sky is illuminated by a full moon, many look upwards in the hope of catching sight of his ephemeral shadow.

The sculptures are complemented by the collection of poems, “Synecdoche,” also by Piga. She conceived these as sound poems: the words are intended to punctuate a rhythmic choreography, which is simultaneously intellectual and musical. In this spirit of constant, studied incompleteness, she also chose to flip traditional roles and interviewed the art critic Ludovico Pratesi. The intra-view that emerges is included in the collection.

Selected works

Gallery

Extras

Exhibited Artists