Maja Arte Contemporanea is pleased to announce the gallery’s first collaboration with the artist Fosca.

Born to a Venetian Mother and a Dutch Father, Fosca is returning to Italy after her debut exhibit at the Correr Museum in Venice in 2015.

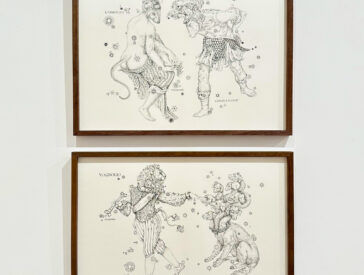

A previously unseen body of works (eleven paintings and thirteen drawings) carries the viewer along an imaginative journey: moving from constellation to constellation by following a thread whose unravelling traces the stars’ paths, the viewer explores an imaginary map of the stars, enlivened by anthropomorphic figures portraying ancient myths. In reinventing these, the artist gives them new life by imbuing them with her original interpretation, culminating, at times, in an unusual happy ending.

“There’s a memory I carry with me wherever I go; it comes from a time when I spent months living at sea when the rocking of the waves became my territory, my source of balance. One night, while we were sleeping at anchor, I lay down to watch the sky; carefree, I was surprised when I caught the stars moving above me, as if someone were rocking the celestial sphere. I was still; the sky was moving. I did not try to identify the constellations, and yet I found mine, as if my memory were projected upon the shards of light. Thus I began to draw a diary, so as to sew together fragments of memory and feelings. Each of these works is a letter to the night sky, to the celestial vault.”

As Flavia Matitti writes in her critical essay published in the exhibition catalogue: “These are the words with which Fosca retraces the experience which, a few years after that night, led her to create a cycle of works dedicated to the constellations. The eleven paintings and the series of drawings in the cycle are here on display for the first time; they are the fruit of intense, passionate, and meticulous work. Fosca began the cycle six years ago, in 2018, and is still in full creative thrust. As she states herself, the theme emerged as a kind of epiphany she had while she was observing the firmament from a boat. It is, perhaps, for this reason that in looking at her starry skies one often has the impression of being before a vast sea crested with waves, a visionary universe belonging to the realm of dreams and to the unconscious.

Indeed, Fosca’s fascination with the stars does not consist in the mere retracing of astronomical phenomena or traditional astrological figures; rather, it uses the celestial vault as a backdrop (in this, she is perhaps inspired by her maternal grandfather, a set designer, one might wonder) on which hopes, memories, fears, dreams, and desires can be projected. Fosca’s constellations are charged with autobiographical echoes and, as such, can be considered psychographs of her states of mind. Her unique personifications of celestial bodies are symbolic images that delicately and ironically allude to lived experiences. At the same time, however, the stars lead into an alternative dimension to reality. This is an occult dimension, one which invites dreams and introspection, yielding an uncovering of the self and of a path to its actualization.

And is this not, after all, what humankind has done since time immemorial: observed the starry sky to find within it a direction and thus divine the future? Across the hemispheres, stars and planets have morphed into gods and heroes, becoming the protagonists of myths and legends. In different places and across cultures, the constellations have changed names and shapes, continually metamorphosing in the unravelling of time.

[…] These works reflect tremendous technical prowess and a profound knowledge of mythology, as well as Fosca’s inexhaustible imagination. In this light, it is always delightful to listen to her narrate the tales of her characters. The lesson that ultimately emerges from this cluster of stories and celestial beings, who stand proud as fluid and wonderfully queer creatures, is to continue to hope and wonder. The stars are the light dream that paves the way.”

Selected works

Gallery

Critical essay

Fosca's Firmament

By Flavia Matitti

Dear Moon, I know that you can speak

and answer questions like a human being,

for I have heard so

from many of the poets.

Giacomo Leopardi, Operette morali, 1824

Translation by Charles Edwardes (1882)

These are the words with which Fosca retraces the experience which, a few years after that night, led her to create a cycle of works dedicated to the constellations. The eleven paintings and the series of drawings in the cycle are here on display for the first time; they are the fruit of intense, passionate, and meticulous work. Fosca began the cycle six years ago, in 2018, and is still in full creative thrust. As she states herself, the theme emerged as a kind of epiphany she had while she was observing the firmament from a boat. It is, perhaps, for this reason that in looking at her starry skies one often has the impression of being before a vast sea crested with waves, a visionary universe belonging to the realm of dreams and to the unconscious.

Indeed, Fosca’s fascination with the stars does not consist in the mere retracing of astronomical phenomena or traditional astrological figures; rather, it uses the celestial vault as a backdrop (in this, she is perhaps inspired by her maternal grandfather, a set designer, one might wonder) on which hopes, memories, fears, dreams, and desires can be projected. Fosca’s constellations are charged with autobiographical echoes and, as such, can be considered psychographs of her states of mind. Her unique personifications of celestial bodies are symbolic images that delicately and ironically allude to lived experiences. At the same time, however, the stars lead into an alternative dimension to reality. This is an occult dimension, one which invites dreams and introspection, yielding an uncovering of the self and of a path to its actualization.

And is this not, after all, what humankind has done since time immemorial: observed the starry sky to find within it a direction and thus divine the future? Across the hemispheres, stars and planets have morphed into gods and heroes, becoming the protagonists of myths and legends. In different places and across cultures, the constellations have changed names and shapes, continually metamorphosing in the unravelling of time.

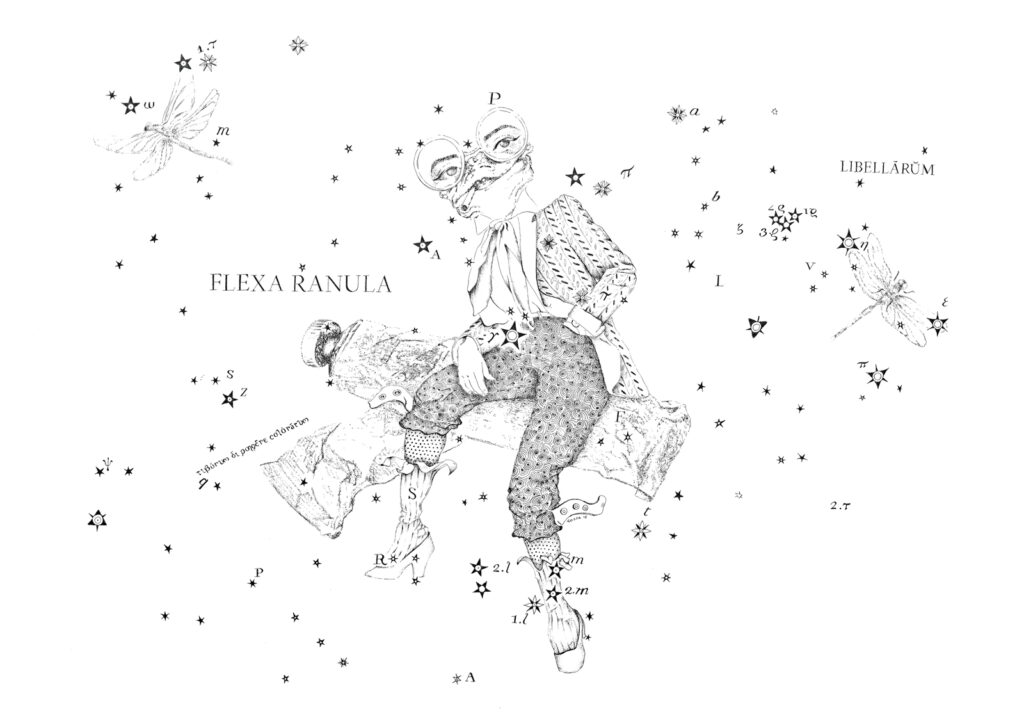

Only a century ago, the International Astronomical Union finally set the number of official constellations to 88, making the production of celestial maps homogeneous. Up to that point, while astronomers were required to calculate the position of stars precisely, they were granted a certain imaginative freedom when it came to drawing the confines of specific clusters of stars or naming the constellations. And so, for instance, French astronomer Jérȏme Lalande, a renowned lover of cats, introduced the cat constellation, Felis, in the firmament. The constellation is no longer in use specifically as a result of a resolution taken by the scientific community in 1922. With her art, Fosca seems to want to reclaim the right to invent new constellations or find novel ways of interpreting those existing.

Born to a Venetian mother and a Dutch father, Fosca studied visual arts in Paris. She attended a graphic design school for five years, while she simultaneously attended anatomy courses at the Fine Arts Academy. She then moved to Venice where she trained at the Bottega del Tintoretto for two years, learning traditional engraving techniques. She subsequently moved to Brazil following her heart; she currently divides her time among Rio de Janeiro, Paris, and Milan.

Fosca’s training in classical engraving played an important part in her artistic evolution, while ancient prints constitute a constant source of inspiration for her. Albrecht Dürer is among her favorite old masters. In 1515, he collaborated with astronomer Conrad Heinfogel to create a famous map of the stars, a woodcut portraying the two hemispheres: northern and southern. In his book entitled La survivance des dieux antiques (1940), Jean Seznec notes that in this work Dürer manages to give new vigor to the personified constellations, which Medieval times had reduced to a banal linearity. Suggestively, Seznec gives Dürer credit for restoring the intimacy and fantastic affairs to the gods and heroes of antiquity. Such qualities are vibrantly present in the deeply humane celestial characters created by Fosca.

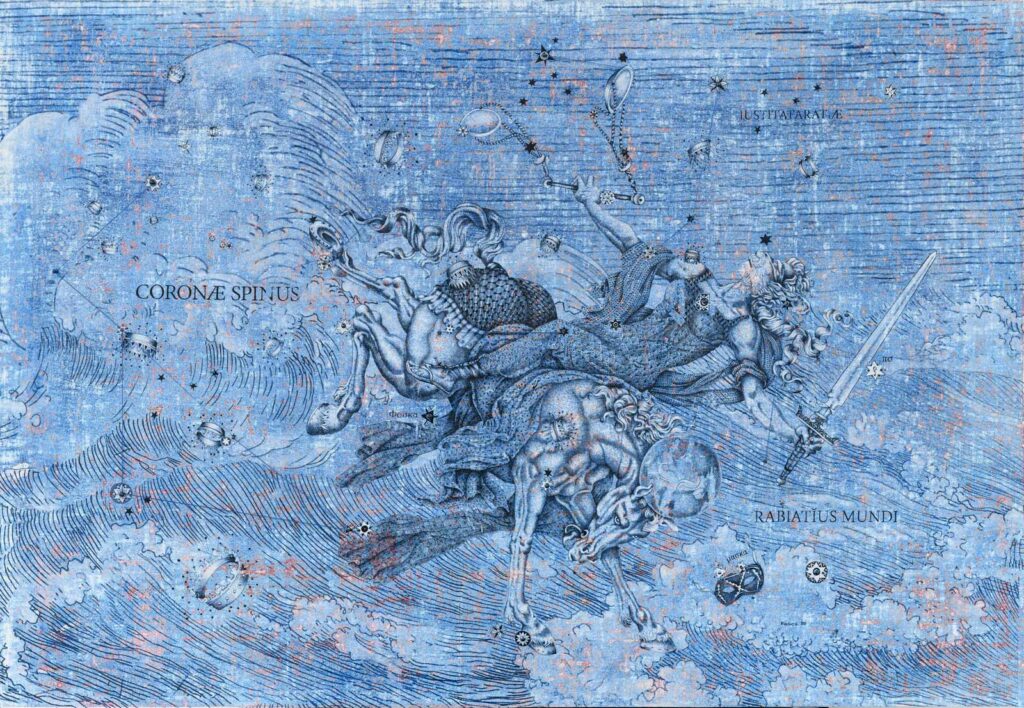

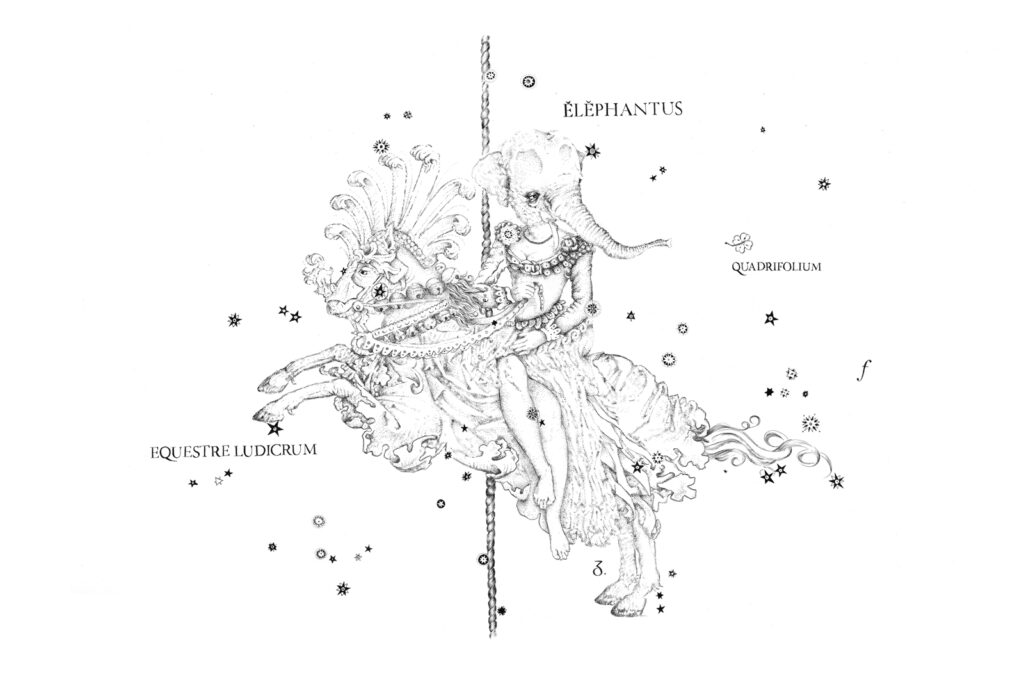

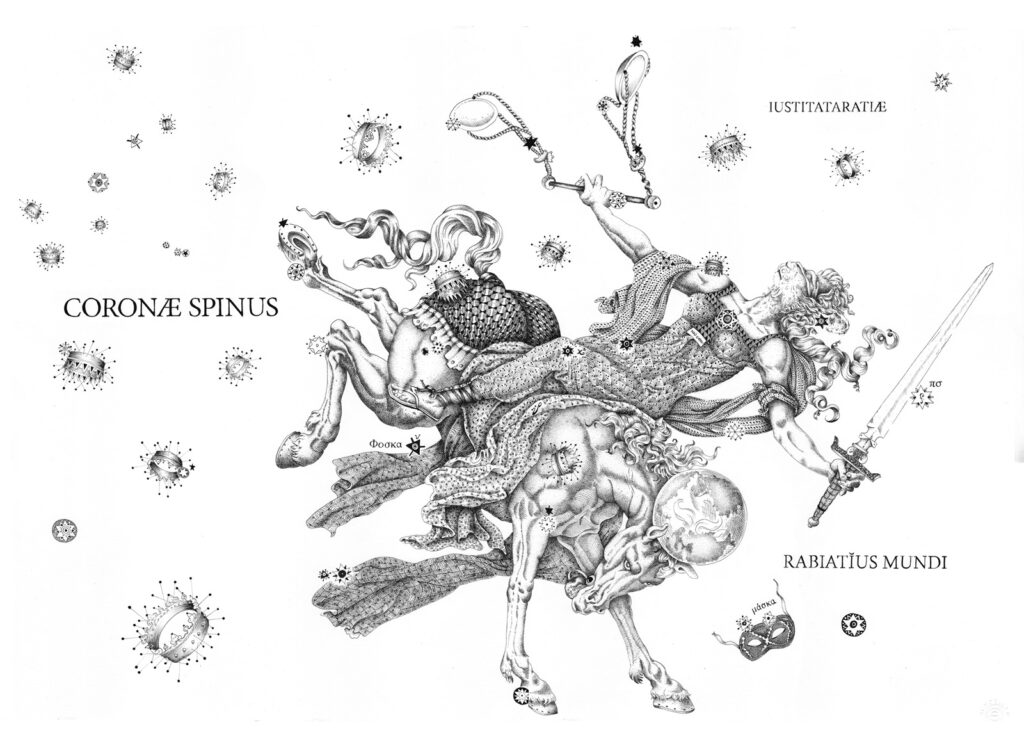

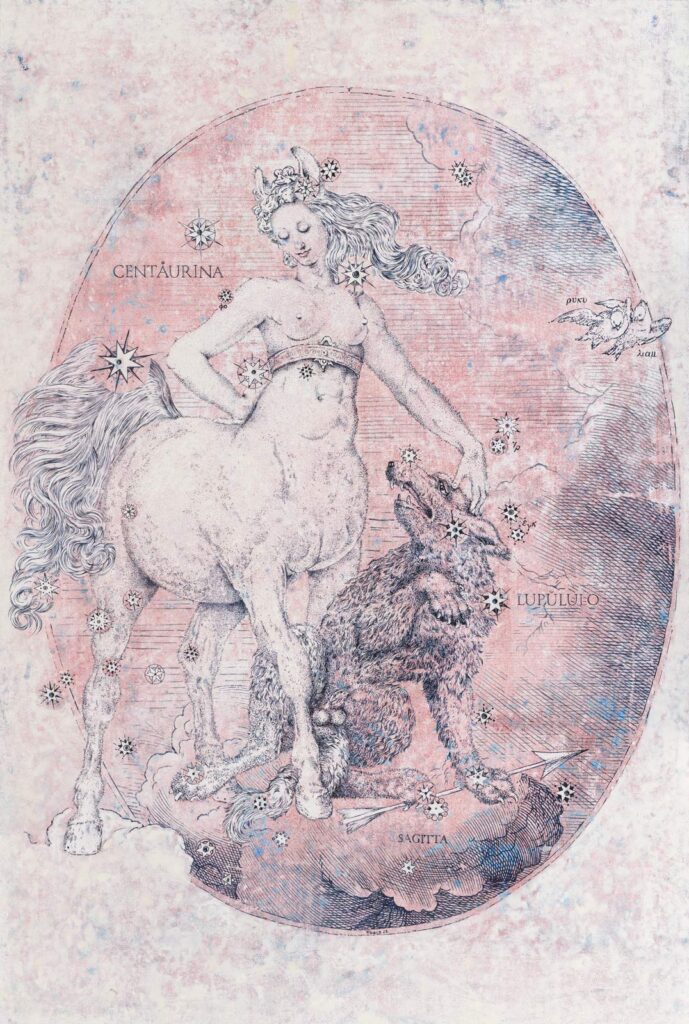

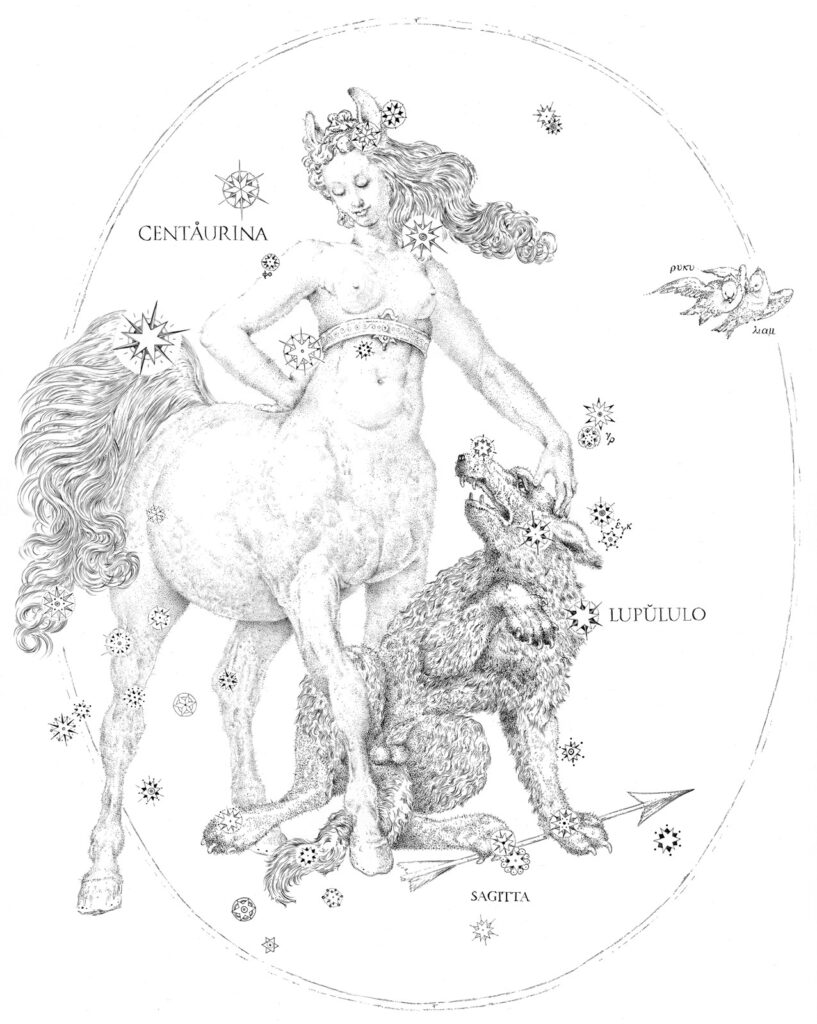

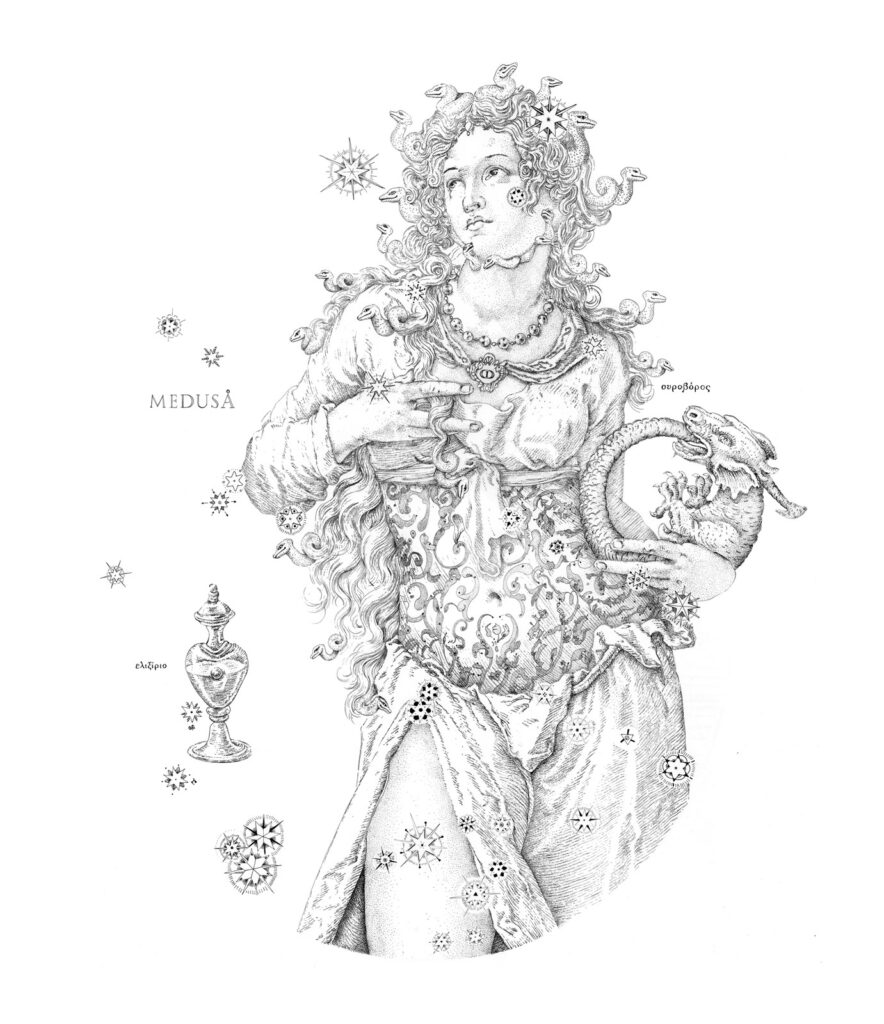

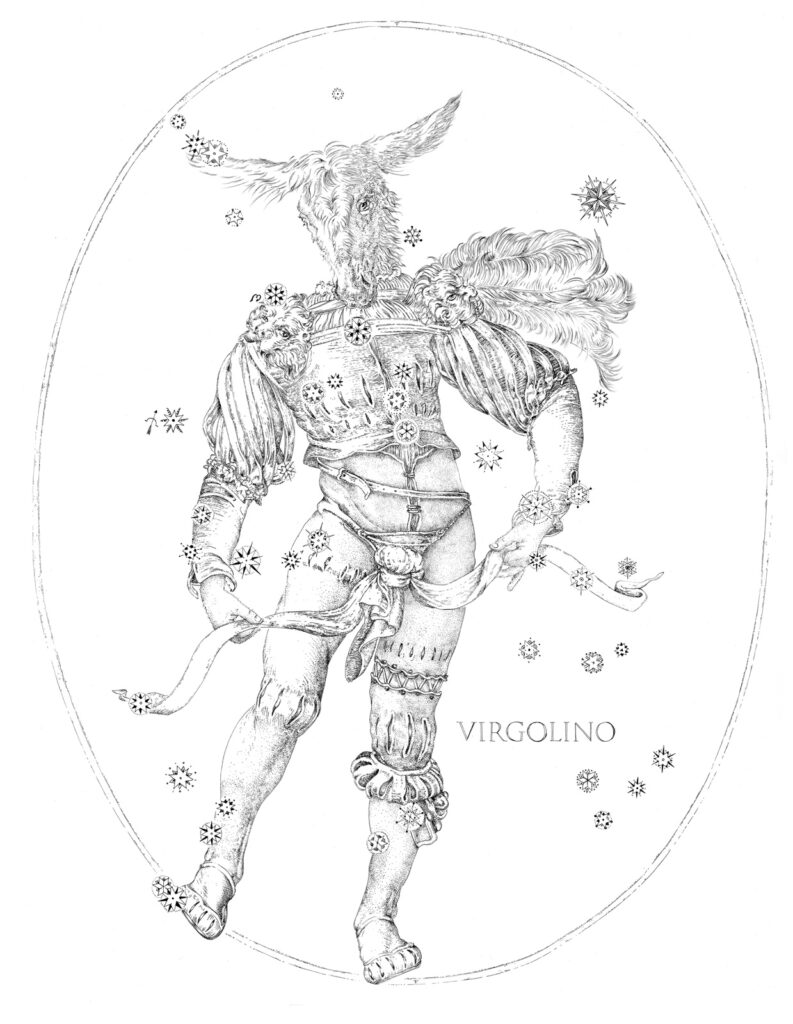

In her cycle dedicated to the constellations, however, Fosca does not use engraving techniques, although one might be fooled in thinking this upon first glance. The works on paper are instead executed with small strokes of Japanese black ink; these are applied to the sheet directly, with a nib, without the aid of a preparatory drawing. The paintings are executed on a thinly-textured linen canvas, which is prepared with plaster and then fixed on a wooden support. The canvas is covered with several overlapping layers of color – blue, red, and white – which are subsequently sanded down to obtain the nuanced and vibrant background hues, so as to evoke the cosmos’s luminescent depth. Some of the stars are then nailed to the plank; in some cases, these are connected with cotton threads and thus become constellations. The threads also physically trace the link between imagination and reality. The execution of these paintings balances moments when the strokes are delicate, intimate, meticulous, with moments where they are aggressive and almost violent. At times, Fosca sands the canvas with such vigor that it tears and has to be sewn back together. In this light, it does not appear to be accidental that the canvas that is most worn and mended is the one dedicated to love: the constellation of Elephantus (2018), which is also the first work in this cycle. The painting portrays a female figure with the head of an elephant, sitting on a carousel horse. The horse symbolizes love’s inconstancy in its unceasing coming and going, bobbing up and down. Elephants are known for their proverbial memory which, Fosca believes, is our most precious asset in that it defines our history and hence our identity. Simultaneously, Elephants’ trunks make them phallic beings, charging the female figure on horse back with mysterious, undefinable undertones.

The artist’s choice to write the names of the stars on her celestial maps in Greek or Latin, as was customary in the past, is also noteworthy. At times, however, she uses modern, invented words, which gain meaning only in other tongues. In Elephantus, for instance, she quips the image of a four-leaf clover, symbolizing luck, with the inscription Quadrifolium, a word that did not exist in ancient Rome. Similarly in the nocturnal Coronae (2020), portraying a wild horse carrying the world on its head and Justice on its back, we read the inscription Coronae Spinus, a combination of invented words that allude to the recent, dark times of Coronavirus. In other instances, Fosca uses her extensive knowledge of languages – she speaks six fluently – to play with words. She uses the Greek alphabet to spell words which phonetically recall a different language. In the work Centaurina (2023), for instance, the Greek phrase ρυκυ λιαμ (“ruku-liam”) appears next to a pair of doves; this is a pun by assonance. When spoken, it sounds like the French term roucouler, which indicates the birds’ cooing but is also used playfully to indicate courtship. In other cases, Fosca has inserted the initials of people who have crossed paths with her within her paintings. All the inscriptions included across the works are used with great imaginative freedom, often creating witty puns which are intended to invite the viewer to take an active, interpretative role.

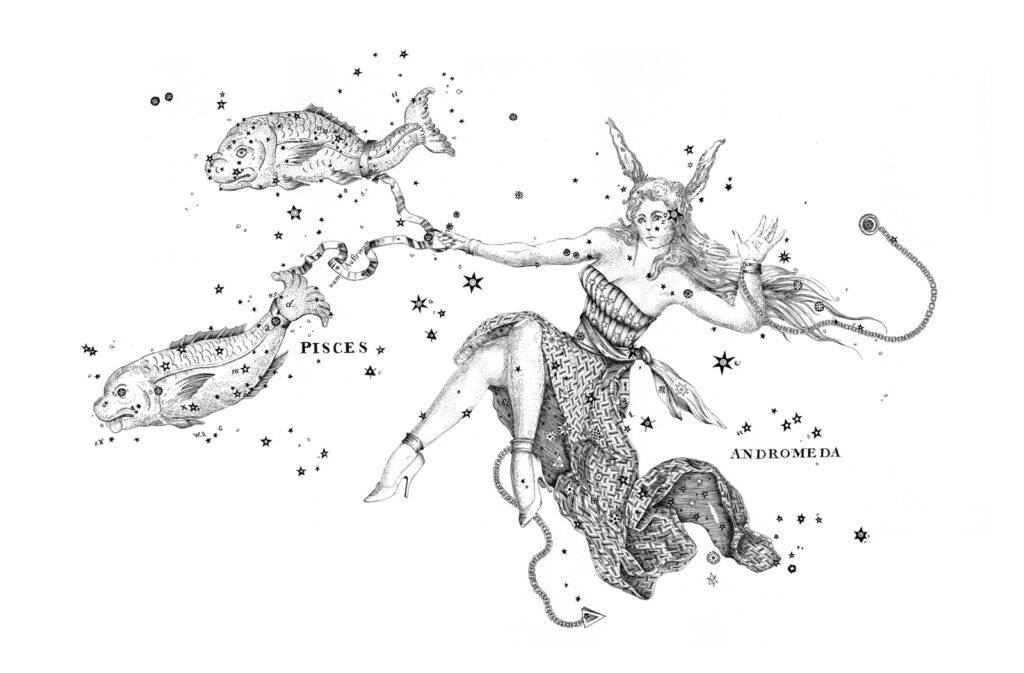

Returning to an exploration of Fosca’s constellations, it is interesting to note that she imagines Andromeda (2020) as a sensual woman, wearing a low-cut dress, stilletos, and nail polish. Andromeda is also a modern, energetic woman. The princess frees herself from the chains tying her to the rock, as an offering to the sea monster who is to devour her. She does not wait for Perseus, the hero, to intervene; she leaves, sporting a lovely pair of rabbit ears on her head, pulled by two fish, reminiscent of the astrological Pisces.

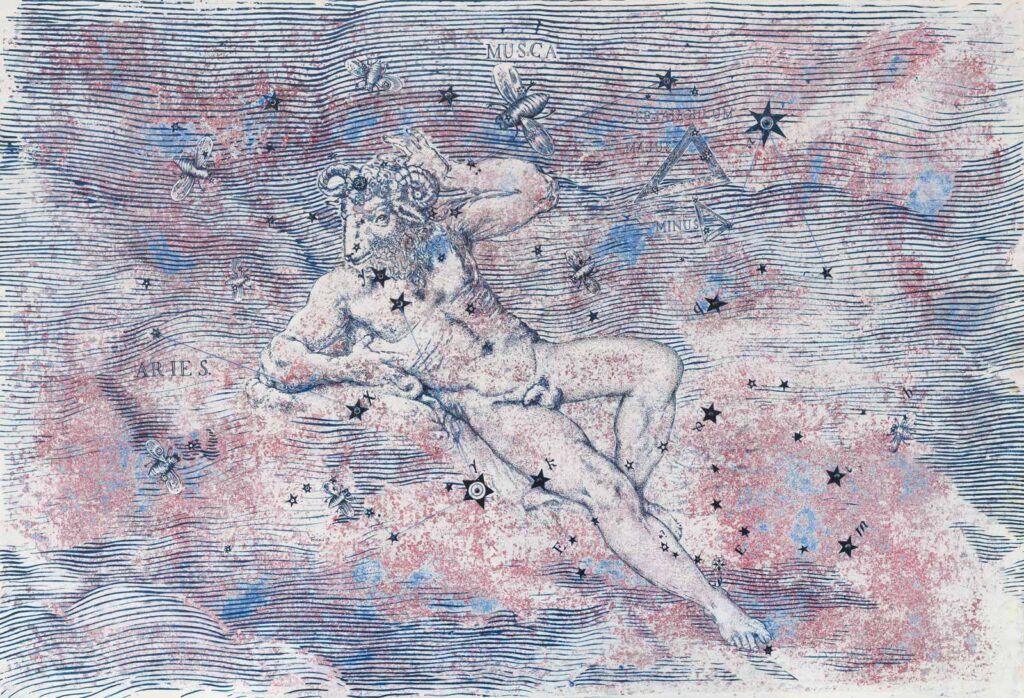

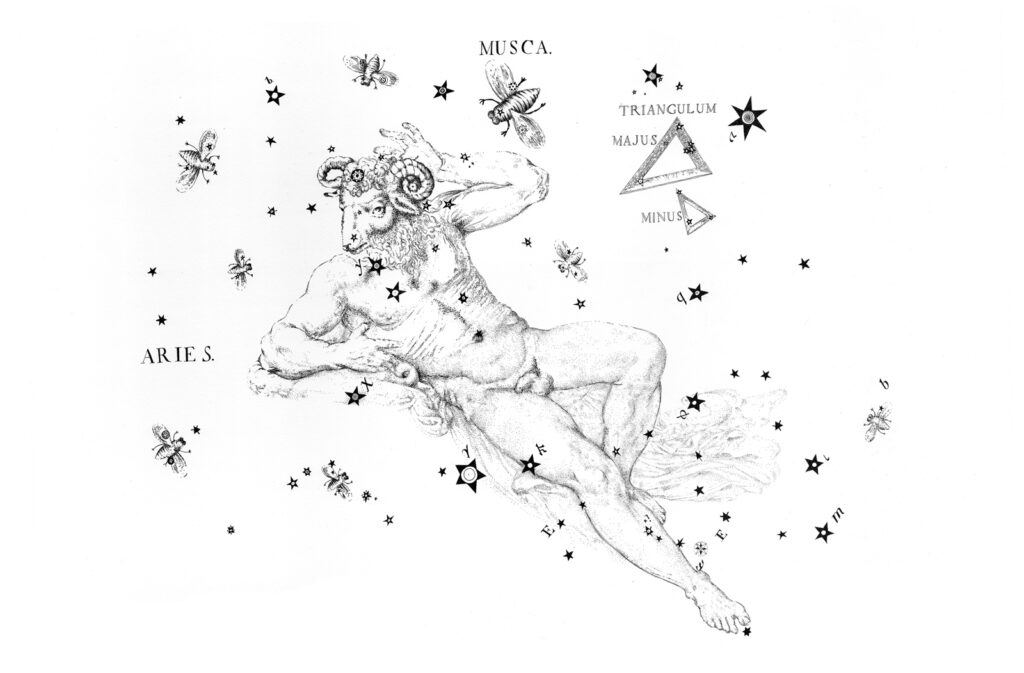

Astrological tradition depicts Aries as a hard, stubborn character. Conversely, Fosca’s Aries (2019) is a reclined man, idly dreaming, his head the only piece resembling an animal.

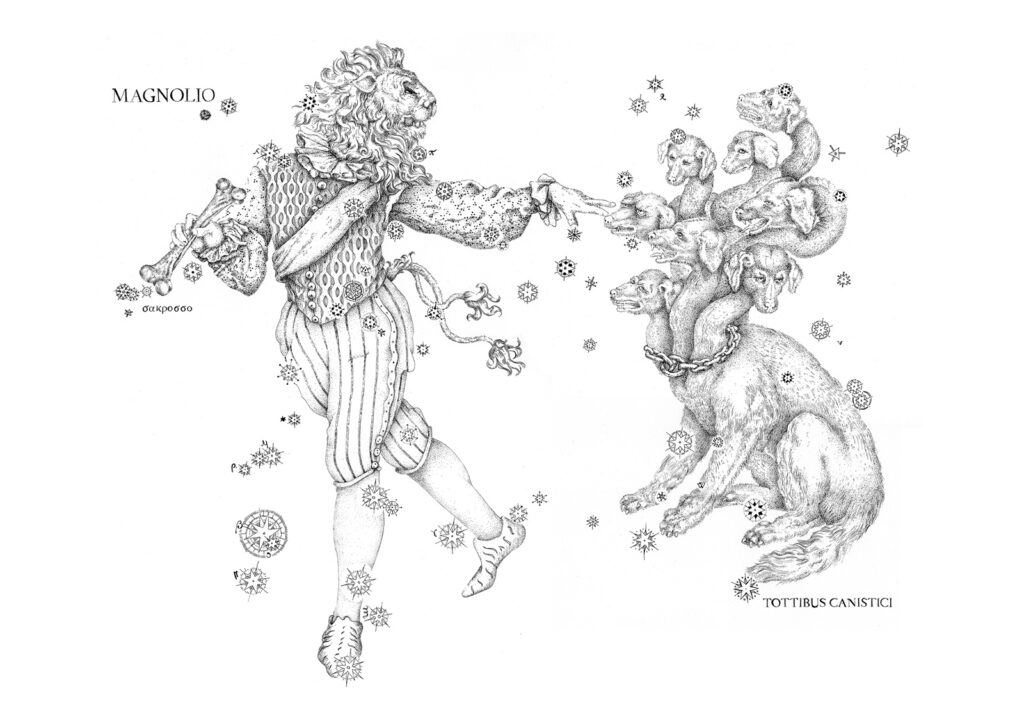

The Leo, entitled Magno Lio (2022) is portrayed with a lion’s head and a human body; in Renaissance clothing, he appears slightly effeminate, with an expression that is both ferocious and kind. He is reminiscent of the Beast as it is represented in Jeanne-Marie Leprince’s late illustrations of the fairy tale, La Belle et la Bête (1756). Magno Lio is depicted taming a monster, which in turn is a strange cross between Hydra and Cerberus. The latter’s eight dog heads each boast a different expression, reflecting Fosca’s love of animals, something she has explored extensively in other works.

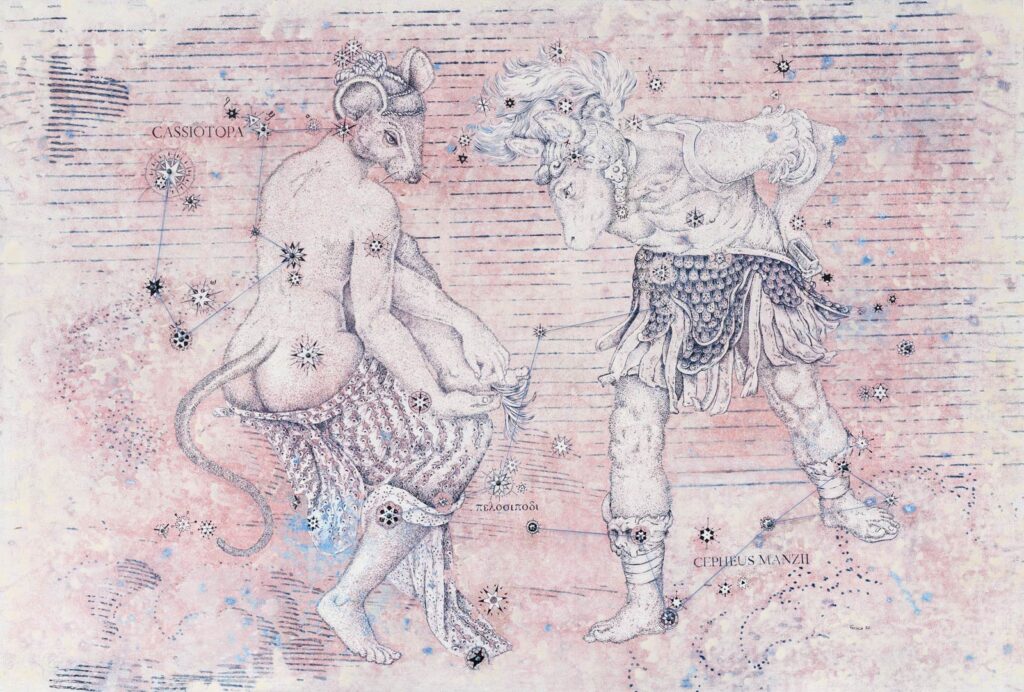

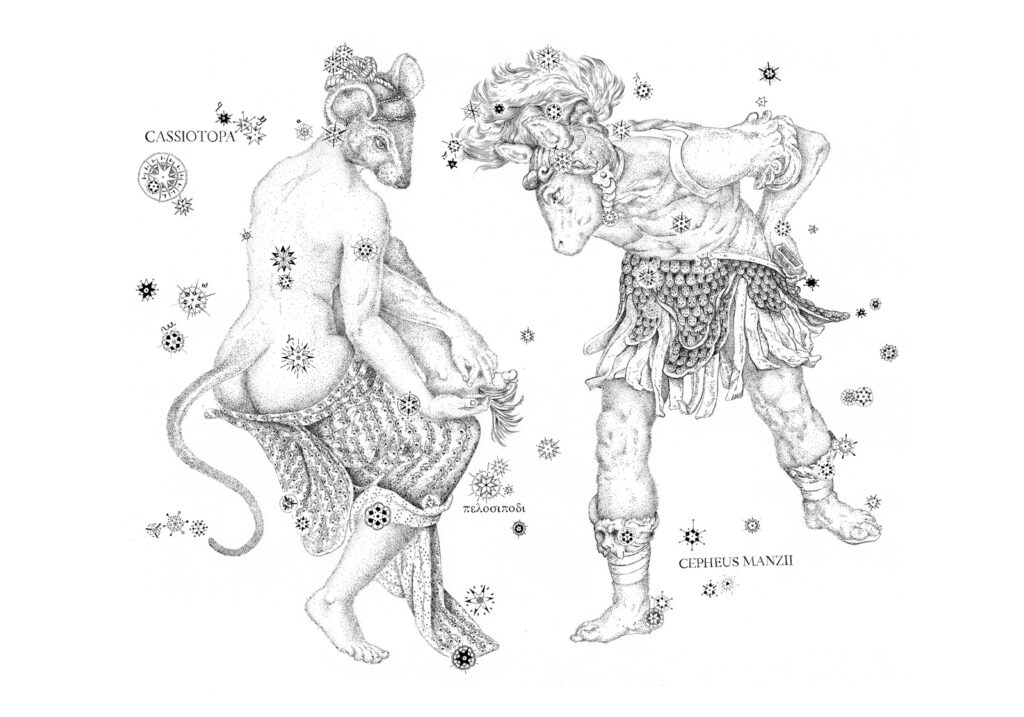

The care with which Fosca indulges on minute details, such as the decorative patterns on the fabrics of clothing, is also remarkable. This is evident, for instance, in the piece entitled Aquarius (2019), which combines the constellation of Aquarius with that of Capricorn and in Cassiotopa (2021-2022), where an anthropomorphic Bull, deprived of horns and sword, observes the foot of a tiny mouse (Cassiotopa, i.e. Cassiomouse) intently, focusing on the hair growing under its sole. The inscription beside it – πελοσιποδι (“pelosipodi – i.e. “hairy foot”) – underscores the focus of the exchange. The scene seems suspended, making it hard to envision what might unfold.

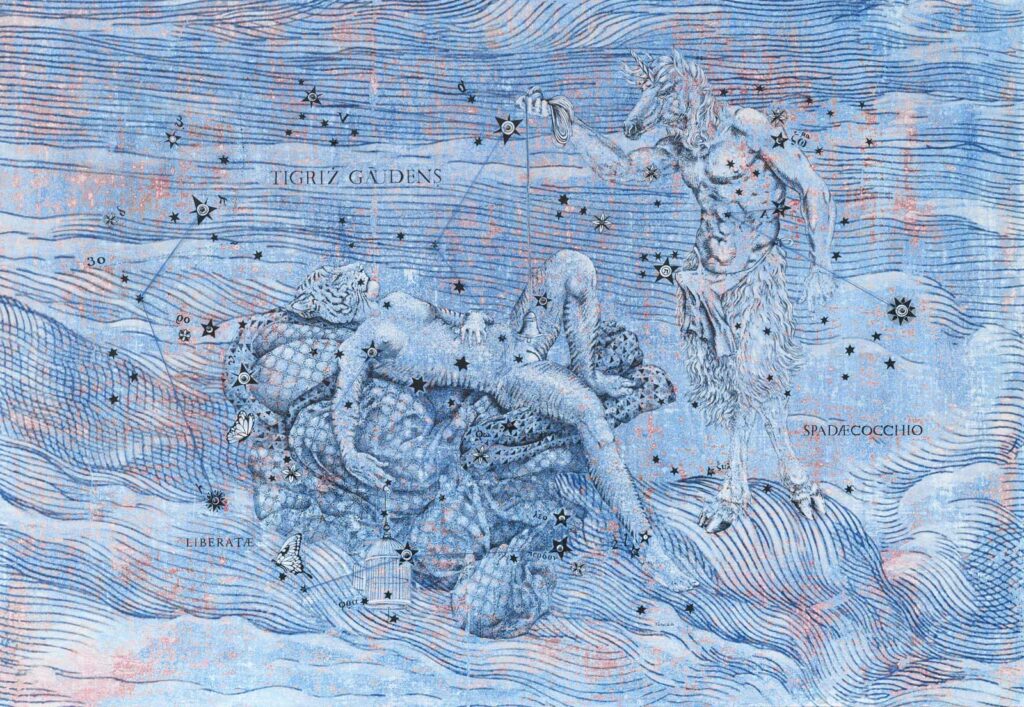

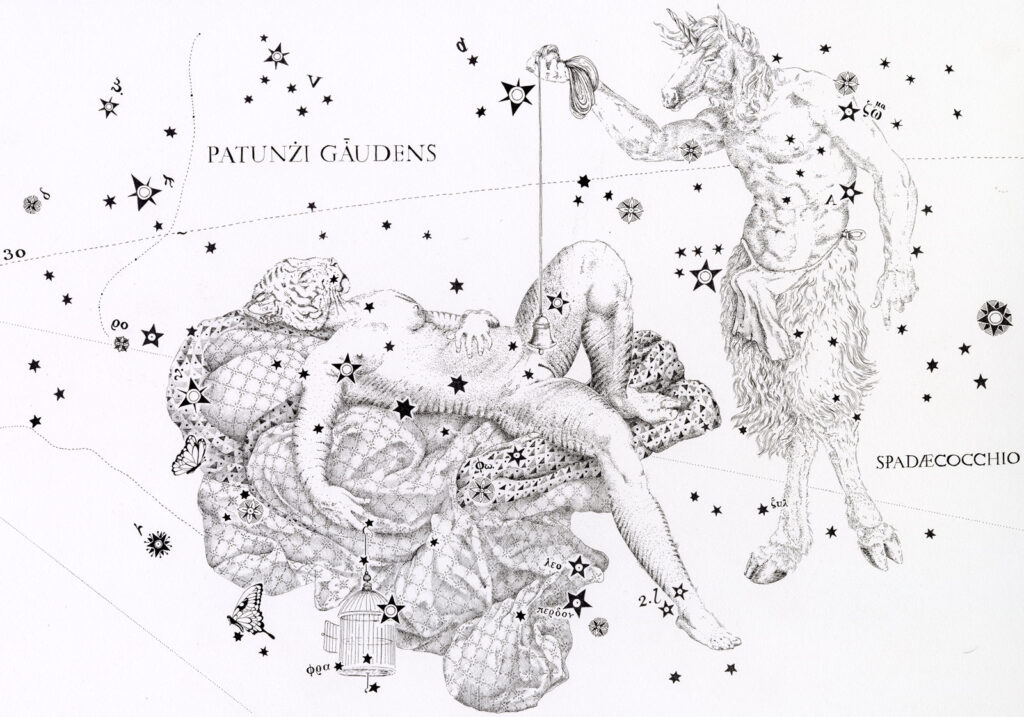

The work Tigriz Gaudens (2021) focuses on the idea of an awakening sensuality. It features two imaginative if deeply human creatures: a tiger-woman and a faun with a unicorn’s head. The two seem to be a reworking of the longstanding tradition of erotic images depicting a sleeping nymph ambushed by a faun.

In the case of Sagittarius, Fosca replaces the conventional centaur with its female counterpart, a Centaurina (2023). Embodying gentle strength, Centaurina keeps the fearsome wolf Fenrir at bay with the sole aid of her kindness. The wolf comes from Germanic mythology, where the gods had to bind him to prevent him from wreaking havoc and causing the world to end.

The zodiac sign of Virgo is reimagined by Fosca as the figure of Virgolino (2022-2023). He is a male virgin, portrayed with a tender expression, donning an imaginative, perhaps theatrical costume. His donkey head is representative of an animal who, Fosca believes, refuses to budge when it does not trust the human hand guiding it and not, as convention has it, because it is stubborn.

The final work in this cycle created thus far is the one dedicated to Medusa (2024). The latter is not conceived as the mythological monster, although her hair has already been changed into snakes by Athena. She is, instead, a Botticellian beauty: delicate and dreamy, in her left hand she holds a ouroboros – the serpent (or dragon) which bites its tail – an ancient symbol of the circularity of time. And, who knows, perhaps Perseus will not kill her. Unlike the two works which were completed immediately before this one, Virgolino and Centaurina, Medusa is not enclosed in an oval space but is free; she is also free from the cotton threads which connect the stars in other works.

In conclusion, these works reflect tremendous technical prowess and a profound knowledge of mythology, as well as Fosca’s inexhaustible imagination. In this light, it is always delightful to listen to her narrate the tales of her characters. The lesson that ultimately emerges from this cluster of stories and celestial beings, who stand proud as fluid and wonderfully queer creatures, is to continue to hope and wonder. The stars are the light dream that paves the way.